Indian Politics Economy Environment

IndianPoliticsEconomyEnvironment

Illegal And Legal Mining In India Harming The Environment

India’s election shows the world’s largest democracy is still a democracy

What went wrong for Modi? - Asia News Network - Asia News Network

'Electoral autocracy': The downgrading of India's democracy

Pressured to withdraw’: BJP accused of intimidation tactics in India polls

Modi's BJP Party Won 240 Seats But Will Need A Coalition To Form A New Government In India Part One

Modi Says BJP Will Not Give Up On Its Ideals Despite Losing Majority In The Indian Parliament Part Two

Narendra Modi Faced Major Upset In India's Most Popular State Of Uttar Pradesh Part Three

392 Palestinian Bodies Have Been Found Recovered From Mass Graves On Hospital Grounds In Khan Younis

An MP, her ex and their dog: Mahua Moitra’s battle with India’s parliament

Outspoken opposition MP hits back after being kicked out, blaming a witch-hunt and vowing ‘I’m not going anywhere’

Mahua Moitra claims the parliamentary ethics committee’s decision to expel her was based on no evidence.

‘Indian democracy fought back’: Modi humbled as opposition gains ground

Journalists have come under attack in India

Several minority groups have complained of discrimination in recent years

More than 600 million Indians voted in the 2019 elections

Mr Modi won a landslide election in 2019

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi

Voters queue up to cast their ballots at a polling station during the seventh and final phase of voting in India’s general election in Dharamsala, India on June 1, 2024.

Mr Modi's government has been accused of targeting minorities

The freedom report criticised the government's response to protests against a controversial citizenship bill

India election results 2024: 3 lessons from Modi’s shocking setback - Vox

Modi’s win in India looks a lot like a loss - Vox

Modi’s domination of Indian politics continues

EXPERT Chris Ogden

Associate Professor in Global Studies, Global Studies Programme, University of Auckland

Chris Ogden's expertise concerns the domestic, foreign and economic politics of India, China, South Asia, East Asia and the Indo-Pacific, as well as the impact of AI on democracy.

12 JUNE 2024

After 44 days of voting involving an electorate of 970 million, India’s general election has finally reached its conclusion. Gaining 240 seats out of a possible 543, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has again beaten his political opponents. For Modi, this is a third consecutive victory for his Hindu nationalist supporters, who will continue to govern India through their wider National Democratic Alliance coalition. Such a record has only been achieved by one other Indian Prime Minister - the country’s founding father Jawaharlal Nehru.

Generation Modi

Central to the BJP’s electoral success has been Modi’s highly charismatic persona. Talismanic, if divisive in some quarters concerning the BJP’s attitude towards India’s Muslim minority, as India’s Prime Minister Modi has maintained exceptionally high approval ratings across his two previous periods in office. For 10 years, these did not drop below 64% and peaked at 93.5%.

Modi’s personal popularity highlights how the BJP has again defied the incumbency effect, whereby most leaders in democratic elections lose voters after gaining power. Instead, even though the BJP did not gain a majority as in previous elections in 2019 (303 seats and 37% of votes) and 2014 (282 seats and 31% of votes), they maintained their vote-base at 37%. Such consistent success was thought to be virtually impossible for a Hindu-dominated party to achieve, especially in a highly ethnically diverse and political complex country such as India.

A pro-capitalist, pro-market, and populist embrace, backed up by the agile use of social media technology and donations from big business are also vital pillars of Modi’s political succour. Each have been vital to the image of a new, richer, returning great power, helping the BJP and Modi to further extend their grip on power. The party’s well-established Hindutva (Hindu-orientated) values have also become the main influence upon India’s domestic and foreign policies. As such, the BJP are now indisputably the centrifugal force of Indian politics and for a generation of Indians, they will only have known their country under Modi’s leadership.

Towards a Hindutva India

Internal political developments reflect the assertion of these Hindutva values. These include the removal in 2019 of Article 370 from the Constitution that revoked the special status of Kashmir or Modi’s personal dedication of the Bhavya Ram Mandir at Ayodhya in 2024, which replaced a mosque of the site. Both actions were long standing manifesto promises, with the BJP claiming that the latter “has rejuvenated our society, … (leading to) a new interest in our history and heritage”. They also inform nationalist discourses of a rapidly resurgent India.

Since 2014, India’s 200 million Muslims have also been targeted. Both the “National Register of Citizens” and the “Citizenship Amendment Act” of 2019 excluded Muslims from the same rights enjoyed by the Hindu majority. Other policies include assembling immense camps for undocumented Muslim migrants in Assam, which are considered by some observers as ‘”the stage just before genocide”’. Legislation has also been introduced to prevent marriages among Muslim men and Hindu women (to inhibit what Hindu nationalists call “love jihad”).

In the new government, we can expect such discrimination to continue to be prominent domestically. This will include efforts to introduce a Uniform Civil Code that would pointedly curtail long-standing religious freedoms across India. The BJP’s reduced number of seats may also embolden party hardliners to accelerate such efforts before they lose power in the future, especially if Modi’s promises of economic success continue to fail to fully materialise by 2029.

A Global Dilemma

Internationally, India is now a well-defined variable within the strategic reckonings of all other major powers. Having the world’s third largest economy and third largest military budget boosts this importance, which attracts highly influential powers including the United States, Russia, China, Japan and Iran. So powerful are these dynamics, which also legitimise the BJP and Hindutva, that they appear to be “anointing” India as a present or future great power.

When combined with (mainly) Western (and Japanese) efforts to actively balance against China in the Indo-Pacific region, India has thus become a necessary and fundamental part of the strategic calculus supporting contemporary great power politics. In these dynamics, the West often willingly discounts the new political – and authoritarian – realities gripping India.

Such inertia can be argued to be emboldening Indian foreign policy, whose intelligence services have been accused of targeting Sikh separatists in Canada, the UK, and the US. The West’s China-myopia therefore makes criticising New Delhi more difficult, whilst allowing other transgressions – be they domestically (the BJP’s attitude towards India’s minorities), or regionally (surgical strikes against her neighbours) – to now potentially escalate and worsen.

This global dilemma applies as much to New Zealand as it does to other larger powers in the region. In much the same way that Wellington walks a tightrope with Beijing that balances positive trade and diplomatic benefits with more negative political and human rights considerations, such a paradox will be more apparent with New Delhi in the next five years.

As India’s influence expands, and with Modi and the BJP’s confidence ever-increasing, how to negotiate walking such a sharp diplomatic razor’s edge will become of greater significance.

- Asia Media Centre

Illegal And Legal Mining In India Harming The Environment

Illegal And Legal Mining In India Harming The Environment

Illegal And Legal Mining In India Harming The Environment Part 1

Illegal And Legal Mining In India Harming The Environment Part 2

Illegal And Legal Mining In India Harming The Environment Part 3

Illegal And Legal Mining In India Harming The Environment Part 4

The Indian Mining Sector: Effects on the Environment & FDI inflows by Pradeep S. Mehta

https://www.oecd.org/env/1830307.pdf

Minerals are non-renewal and limited resources and constitute vital raw materials in a number of basic and important industries. The extraction of mineral from nature often creates imbalances, which adversely affect the environment. The key environmental impacts of mining are on wildlife and fishery habitats, the water balance, local climates and the pattern of rainfall sedimentation, the depletion of forests and the disruption of the ecology. Therefore management of a country's mineral resources must be closely associated with her overall economic development and environmental protection and preservation strategy.

India has huge mineral resources. Thus the mining industry us a very important industry in India, It only opened up to foreign investment in the 1990's, and the floq2wof foreign investment in the mining sector has been very low dure to restrictions. Moreover, in India the mining sector is facing several challenged, which are:

Massive investment required in exploration and the up-gradation of technology.

Mitigation of environmental degradation due to mining

Adaption of environment friendly technology Tackling of social issues like displacement of the population, marginalisation of local communities and economic disparities in mining areas

Rehabilitation of closed and abandoned mine sites

The India Government, at both central and the state level, has to address these issues by formulating appropriate policies and effectively implementing them for the overall development of the sector which is environmentally sustainable

How Mining Affects the Environment

1. Air. Surface mines may produce dust from blasting operations and haul roads. Many coal mines release methane, a greenhouse gas. Similar operations with insufficient safeguards in place, have potential to pollute the air with heavy metals, sulphur dioxide, and other pollutants.

2. Water. The Mining sector uses large quantities of water, though some mines do reus much of the water intake. Mining throws sulphide-containing mineral into the air, where they oxidise and react with water to form sulphuric acid. This together with various trace elements impacts groundwater, both from the surface and underground mines.

3. Land. The movement of rocks due to mining activities and overburden (material overlying a mineral deposit that must be removed before mining in thr case of surface mines impacts land severely. These impacts maybe temporary where the mining company returns the rock and overburden tot he pit from which they were extracted. Many copper mines, for example, extract ore that contains less than 1%f copper

4. Health and safety. Mining operations from extremely hazardous to being as safe or as dangerous as any other large scale industrial activity. Underground mining i generally more hazardous than surface mining because of poorer ventilation, and the danger of rockfalls. The greatest health risks arise from dust, which lead to respiratory problems, and from exposure to radiation (where applicable)

Source: Sustainable Development Networking Programme (SDNP, India)

The Indian Mining Sector

The mining sector of India contributes approximately four percent tot he Gross Domestic Product (ODP) and is one of the largest employers in India, employing more than one million workers which is around four percent of the total Indian workforce, India produces 89 minerals, out of which 4 are mineral fuels,11 metalic, 52 non-metalic minerals.

In 1998-90 the total value of mineral production )excluding atomic minerals) was Rs404768 million ($8390.70 million at Rs. 48.24/$1 exchange rate).

There are more than 3,500 mining operations in India, most of which are on a very small scale and 300 of which are underground in the non-fuel sector,

The mining industry in India is dominated by government corporations (or Public Sector Units - SCUs as they are known in India) which employ more than 90 percent of the mining industry's workforce,

The Indian mining sector grew at an average annual rate of 8.4 percent between 1980/81 and 1991/92 and only 3.3 percent between 1992/93 and 1999/2000. (Economic Survey 2000-01)

Out of Control

Mining, Regulatory Failure, and Human Rights in India

https://www.hrw.org/report/2012/06/14/out-control/mining-regulatory-failure-and-human-rights-india

Summary

India’s mining industry is an increasingly important part of the economy, employing hundreds of thousands of people and contributing to broader economic growth. But mining can be extraordinarily harmful and destructive if not properly regulated—as underscored by a long list of abuses and disasters around the world. And because of a dangerous mix of bad policies, weak institutions, and corruption, government oversight and regulation of India’s mining industry is largely ineffectual. The result is chaos.

The scale of lawlessness that prevails in India’s mining sector is hard to overstate. Even government officials acknowledge that the mining sector faces a myriad of problems, including widespread “illegal mining.” Generally speaking, that refers to cases where operators harvest resources they have no legal right to exploit. Official statistics indicate that there were more than 82,000 instances of illegal mining in 2010 alone—an annual rate of 30 criminal acts for every legitimate mining operation in the country. But this report argues that an even bigger problem is the failure of key regulatory mechanisms to ensure that even legal mine operators comply with the law and respect human rights.

Global standards of industry good practice have evolved to recognize that unless mine operators exercise caution and vigilance, direct harmful impacts on surrounding communities are likely. In India and around the world, experience has shown that without effective government regulation, not all companies will behave responsibly. Even companies that make serious efforts to do so often fall short without proper government oversight.

This report is not a targeted investigation of particular companies or headline-grabbing “megaprojects.” Rather, it describes how and why key Indian public institutions have broadly failed to oversee and regulate mining firms and links some of these regulatory failures to human rights problems affecting mining communities. The report uses in-depth case studies of iron mining in Goa and Karnataka states to illustrate broader patterns of failed regulation, alleged corruption and community harm. It shows how even mines operating with the approval of government regulators are able to violate the law with complete impunity. Finally, it offers practical, straightforward recommendations on how the Indian government could begin to address these problems.

International law obliges India’s government to protect the human rights of its citizens from abuses by mining firms and other companies. India has laws on the books that are designed to do just that, but some are so poorly designed that they seem set up to fail. Others have been largely neutralized by shoddy implementation and enforcement or by corruption involving elected officials or civil servants. The result is that key government watchdogs stand by as spectators while out-of-control mining operations threaten the health, livelihoods and environments of entire communities. In some cases public institutions have also been cheated out of vast revenues that could have been put towards bolstering governments’ inadequate provision of health, education, and other basic services.

In iron mining areas of Goa and Karnataka states visited by Human Rights Watch, residents alleged that reckless mine operators had destroyed or contaminated water sources they depend on for drinking water and irrigation. In some cases, miners have illegally heaped waste rock and other mine waste near the banks of streams and rivers, leaving it to be washed into local water supplies or agricultural fields during the monsoon rains. This can render water sources unsafe and decrease agricultural fertility. Rather than seek to mitigate any damage, some mine operators puncture the local water table and then simply discard the vast torrents of water that escape—permanently destroying a resource that whole communities rely on.

In some communities visited by Human Rights Watch, farmers complained that endless streams of overloaded ore trucks passing along narrow village roads had left their crops coated in thick layers of metallic dust, destroying them and threatening economic ruin. In some areas, Human Rights Watch witnessed lines of heavily-laden mining trucks several kilometers long grinding along narrow, broken roads and leaving vast clouds of dust in their wake. Some residents pointed to the same metallic dust coating their homes and even local schoolhouses, and worried about the potential for serious respiratory ailments and other health impacts that scientific studies have associated with exposure to mine-related pollution. In some of these communities, people have suffered intimidation or violence for speaking out about these problems. All of these allegations echo common complaints about mining operations across many parts of India.

Some of India’s mining woes have their roots in patterns of corruption or other criminality. For instance, this report describes how mining magnate Janardhana Reddy allegedly used his ministerial position in the state government of Karnataka to extort huge quantities of iron ore from other mine operators—using government regulators as part of his scheme. The evidence shows that state government agencies in Karnataka alone may have been cheated out of billions of rupees (hundreds of millions of dollars) in revenue—depriving the state of funds that could have been put towards the improvement of the state’s dismal health care and education systems.

As lurid as some of India’s mining-related corruption scandals have been, Human Rights Watch believes that the more widespread problem is government indifference. Even in Karnataka, ineffectual regulation played a key role in allowing criminality to pervade the state’s mining sector. And many of the alleged human rights abuses described in this report result not from patterns of corruption or criminality but from the government’s more mundane failure to effectively monitor, let alone police, the human rights impacts of mining operations. Many public officials openly admit that they have no idea how prevalent or how serious the problems are. In effect, India’s government often leaves companies to regulate themselves—a formula that has consistently proven disastrous in India and around the world.

In some cases the harm communities have suffered because of nearby mining operations is well-documented by scientific studies or research by Indian activists. But in many others, the data simply does not exist to confirm or refute alleged harms or their links to mining operations. Some community activists may wrongly attribute health or environmental problems to nearby mining operations. Others may fail to perceive a link that does in fact exist. All of this uncertainty is part of the problem—in far too many cases, government regulators fail to determine whether companies are behaving legally or responsibly, or whether they are causing harm to their neighbors.

India’s tiny Goa state encapsulates all of these problems. State government regulators there admit they have no real idea whether individual mining firms are complying with the law, and the evidence shows that many are not. Activists and even the current chief minister allege widespread illegalities and, surprisingly, local mining industry officials do not deny such allegations. One company executive interviewed by Human Rights Watch spoke of “chaos and corruption” and a “total lack of governance” in the state’s mining sector. A spokesperson for the Goan mining industry estimated that nearly half of all mining in the state violates various laws and regulations.

The problems in Goa reflect nationwide failures of governance in the mining sector. From initial approval to ongoing oversight, the mechanisms in place to regulate and oversee India’s mining industry simply do not work.

The only mechanism directly tasked with weighing a proposed new mine’s potential impacts on the human rights and livelihoods of affected communities is the environmental clearance process, usually undertaken by the central government’s Ministry of Environment and Forests (MOEF). Despite its name, the environmental clearance regime is explicitly empowered to consider impacts on local communities and their rights, not just environmental issues. But the process is hopelessly dysfunctional.

Often, clearances are granted or denied almost entirely on the strength of Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) reports commissioned and paid for by the very companies seeking permission to mine. By design, the reports give short shrift to the issue of human rights and other community impacts, focusing on purely environmental concerns. Many do not even explicitly mention the responsibilities of mining firms to respect the human rights of affected communities. Some companies treat mandatory public consultations around the reports as an irritating bureaucratic hurdle rather than an important safeguard for affected communities.

Worse still, there is considerable evidence that that these crucial EIA reports are often extremely inaccurate, are deliberately falsified, or both. In some cases, reports incorrectly state that issues of potential regulatory concern—the presence of rivers or springs, for instance—simply do not exist. Sometimes important conclusions are simply cut and pasted from one report to the next by authors who appear to assume that regulators will not bother to read what they have written. In the most notorious example of this phenomenon, a mine in Maharashtra state received clearance to proceed even though its EIA report contained large amounts of data taken verbatim from a similar report prepared for a bauxite mine in Russia. Officials’ failure to detect such blatant falsification is emblematic of the broader absence of meaningful government oversight.

Unsurprisingly, under this framework, mining projects are almost never denied environmental clearance. And once a mine is operational it experiences comparably lax government oversight of its actual compliance with the terms of those clearances. A few dozen officials across India are responsible for monitoring thousands of mines and other projects nationwide and are rarely able to make site visits to any of them. Instead, they rely almost entirely on compliance reports provided by mining companies themselves.

India’s Ministry of Environment and Forests is singled out for detailed criticism in this report. This is not because its failures are greater than those of other government institutions with responsibilities towards the mining sector, but because the success of its efforts is essential to any hope of minimizing mining sector human rights problems. Human Rights Watch believes that fixing the environmental clearance regime and other processes linked to the ministry are among the most promising immediate and concrete steps the central government could take to safeguard the human rights of mining-affected communities.

Increasingly, the chaos in India’s mining sector has deep political and economic implications. In 2011, scandals rooted in public revelations about corruption and abuse in the mining sector overtook the state governments in both Karnataka and Goa. Karnataka’s chief minister was forced to resign and much of the state’s mining industry was effectively shut down by a belated government crackdown, at vast economic cost. In March 2012, Goa’s state government was voted out of office partly due to rising public anger about scandals plaguing that state’s mining industry.

India’s central government should not succumb to the temptation to treat the problems in Goa and Karnataka as isolated issues. Both states’ mining debacles reflect nationwide problems that need to be treated as such. Underscoring that point, in early 2012 potentially explosive investigations into the mining industry were underway in Jharkhand and Orissa states.

Admittedly, the chaos in India’s mining industry has some of its roots in much broader patterns of corruption and poor governance that are not easily solved. Nonetheless, there are pragmatic steps the Indian government could take to repair some of the most glaring regulatory failures. Problems would still remain absent broader improvements in governance, but the reforms recommended by this report would give determined regulators more appropriate tools to do their jobs and make it harder for abusive companies to escape scrutiny. The measures proposed in this report would also have impacts far beyond the mining industry, since some of the same broken institutions also regulate and oversee other potentially harmful industries. At this writing, India’s parliament was considering a proposed new mining law that is in some respects remarkably progressive—but it does not seek to address the core problems described in this report.

The government should dramatically improve the process for considering proposed new mining projects, to ensure that it comprehensively and credibly considers possible human rights and other community impacts. This means mandating a greater and more explicit focus on human rights in the environmental clearance process. It also means having adequate numbers of regulators who can take far more time and care in evaluating new proposals, including through site visits wherever appropriate. The government should also end the practice of requiring companies to select and pay the consultants who produce their Environmental Impact Assessment reports—this creates a glaring conflict of interest that recent government efforts at improved quality control do not adequately address.

It is also important for the government to assess how much damage has already been done under the current, woefully inadequate regime. Human Rights Watch recommends a comprehensive study of the Environmental Impact Assessment reports underpinning the clearances for all existing mines in the country, to determine how many incorporate blatantly erroneous or fraudulent data. In late 2011 Goa’s state government helped sponsor an independent effort to do just this; if successful it could serve as a model for other states and for the central government. Wherever deliberate falsification of EIA data is discovered, those responsible should be appropriately prosecuted. In all cases where materially important errors are discovered, mining operations should be halted pending the completion of a new assessment.

Human Rights Watch also calls on the central government to improve the system for monitoring the human rights and environmental impacts of existing mines. In particular, the capacity and mandate of the Ministry of Environment and Forests to actively monitor compliance with the terms of the environmental clearances underpinning mines and other projects needs to be dramatically improved.

At the state level, governments in mining areas should work to bolster the mandates and capacity of key institutions, including the pollution control boards and mines departments, that have often failed to contribute to effective oversight of the mining sector. They should also work to establish strong and effective Lokayukta (anti-corruption ombudsman) institutions, or bolster the institutions they already possess. Where any or all of these institutions require additional financial resources, governments should consider earmarking a portion of revenues earned from the mining industry for that purpose.

Key Recommendations

The key recommendations to the Indian government are explained in more detail at the end of this report, in the section titled “Reining in the Abuse: Practical Steps Forward for India’s Government.”

To the Government of India

- Ensure that regulatory officials focus attention on potential human rights and other community impacts of proposed new mines, either through the existing Environmental Impact Assessment process or through a new assessment process focused exclusively on human rights impacts.

- End the practice of requiring mining firms to select and pay the consultants who carry out their Environmental Impact Assessment reports. Assessments could be funded through a general fund paid for by mining firms but under government control.

- Empower the Expert Appraisal Committees to carry out a more thorough review of the potential negative impacts of proposed new mining projects, including through frequent site visits. This will require substantial additional staffing and other resources as well as a slower rate of project consideration and approval.

- Draft rules requiring a more thorough and detailed consideration of the results of any mandatory public consultations required by the approvals process for a new project.

- Impose robust sanctions, including criminal prosecution where appropriate, on mining companies and consultants whose Environmental Impact Assessment reports contain materially important data that is falsified or negligently incorrect.

- Initiate an independent review of the Environmental Impact Assessment reports underpinning all existing mines, with a view to determining how many of them are based on materially false or misleading data. Temporarily halt mining operations whose Environmental Impact Assessment reports contain materially important false data, require their operators to reapply for clearance, and appropriately sanction those responsible.

- Empower and instruct the Ministry of Environment and Forests to carry out more thorough and proactive monitoring and oversight of existing mining projects, including by providing the staff and other resources necessary to fulfill this role effectively.

- Explore ways to ensure that institutions accredited to carry out Environmental Impact Assessments are also well trained in human rights principles and in global best practices for human rights impact assessments in the mining sector.

To India’s State Governments

- Consider the creation of new Lokayukta institutions, or bolster those offices already in existence, ensuring that they benefit from adequate levels of independence, resources and human capacity along the lines of Karnataka State’s institutional model.

- Strengthen key state-level regulatory institutions including mines ministries and pollution control boards to ensure that they are able to contribute effectively to robust oversight of mining operations. To the extent resources or capacity-building is required, consider earmarking some state government revenues derived from mining activities for this purpose.

To the United Nations Special Rapporteurs on the Right to Health and on the Right to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation

- Request to visit India to further evaluate the impact of inadequate government regulation of the mining sector on the rights of Indians to health and to water.

India election results 2024: 3 lessons from Modi’s shocking setback - Vox

India just showed the world how to fight an authoritarian on the rise

Three big lessons from Narendra Modi's shocking underperformance in the 2024 election.

by Zack Beauchampm Jun 7, 2024

Trinamool Congress party members are celebrating the victory in the Lok Sabha election in Kolkata, India, on June 4, 2024.

Sudipta Das/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi is, by some measures, the most popular leader in the world. Prior to the 2024 election, his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) held an outright majority in the Lok Sabha (India’s Parliament) — one that was widely projected to grow after the vote count. The party regularly boasted that it would win 400 Lok Sabha seats, easily enough to amend India’s constitution along the party's preferred Hindu nationalist lines.

But when the results were announced on Tuesday, the BJP held just 240 seats. They not only underperformed expectations, they actually lost their parliamentary majority. While Modi will remain prime minister, he will do so at the helm of a coalition government — meaning that he will depend on other parties to stay in office, making it harder to continue his ongoing assault on Indian democracy.

So what happened? Why did Indian voters deal a devastating blow to a prime minister who, by all measures, they mostly seem to like?

India is a massive country — the most populous in the world — and one of the most diverse, making its internal politics exceedingly complicated. A definitive assessment of the election would require granular data on voter breakdown across caste, class, linguistic, religious, age, and gender divides. At present, those numbers don’t exist in sufficient detail.

But after looking at the information that is available and speaking with several leading experts on Indian politics, there are at least three conclusions that I’m comfortable drawing.

First, voters punished Modi for putting his Hindu nationalist agenda ahead of fixing India’s unequal economy. Second, Indian voters had some real concerns about the decline of liberal democracy under BJP rule. Third, the opposition parties waged a smart campaign that took advantage of Modi’s vulnerabilities on the economy and democracy.

Understanding these factors isn’t just important for Indians. The country’s election has some universal lessons for how to beat a would-be authoritarian — ones that Americans especially might want to heed heading into its election in November.

A new (and unequal) economy

Modi’s biggest and most surprising losses came in India’s two most populous states: Uttar Pradesh in the north and Maharashtra in the west. Both states had previously been BJP strongholds — places where the party’s core tactic of pitting the Hindu majority against the Muslim minority had seemingly cemented Hindu support for Modi and his allies.

One prominent Indian analyst, Yogendra Yadav, saw the cracks in advance. Swimming against the tide of Indian media, he correctly predicted that the BJP would fall short of a governing majority.

Traveling through the country, but especially rural Uttar Pradesh, he prophesied “the return of normal politics”: that Indian voters were no longer held spellbound by Modi’s charismatic nationalist appeals and were instead starting to worry about the way politics was affecting their lives.

Yadav’s conclusions derived in no small part from hearing voters’ concerns about the economy. The issue wasn’t GDP growth — India’s is the fastest-growing economy in the world — but rather the distribution of growth’s fruits. While some of Modi’s top allies struck it rich, many ordinary Indians suffered. Nearly half of all Indians between 20 and 24 are unemployed; Indian farmers have repeatedly protested Modi policies that they felt hurt their livelihoods.

“Everyone was talking about price rise, unemployment, the state of public services, the plight of farmers, [and] the struggles of labor,” Yadav wrote.

According to Pavithra Suryanarayan, a political scientist at the London School of Economics, this sort of discontent was quite visible on the ground. In the months prior to the election, she conducted research in three regions of India on public perceptions of Modi’s economic policy. She found that voters blamed Modi for three major economic policy mistakes: a failed attempt to replace cash payments with electronic transfers, a disastrous Covid-19 response, and a tax on goods and services that favored the wealthy over small businesses.

“These three economic calamities compounded into general dissatisfaction with economic mismanagement,” she tells me.

In general, she believes there’s a sense among Indian voters that the BJP saw them as “recipients of schemes” rather than “rights-bearing citizens,” meaning that Modi’s government put various policy experiments ahead of basic capabilities to provide good jobs, access to health care, and high-quality education.

Interestingly, many of these policies are not new. We’re several years out of the pandemic, and the demonetization experiment took place all the way back in 2016. Indian voters know that Modi has been in power for 10 years and seem to have turned against the incumbent based on a general sense that he’s botched certain elements of his governing agenda.

“We know for sure that Modi’s strongman image and brassy self-confidence were not as popular with voters as the BJP assumed,” says Sadanand Dhume, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute who studies India.

The lesson here isn’t that the pocketbook concerns trump identity-based appeals everywhere; recent evidence in wealthier democracies suggests the opposite is true. Rather, it’s that even entrenched reputations of populist leaders are not unshakeable. When they make errors, even some time ago, it’s possible to get voters to remember these mistakes and prioritize them over whatever culture war the populist is peddling at the moment.

Liberalism strikes back

The Indian constitution is a liberal document: It guarantees equality of all citizens and enshrines measures designed to enshrine said equality into law. The signature goal of Modi’s time in power has been to rip this liberal edifice down and replace it with a Hindu nationalist model that pushes non-Hindus to the social margins. In pursuit of this agenda, the BJP has concentrated power in Modi’s hands and undermined key pillars of Indian democracy (like a free press and independent judiciary).

Prior to the election, there was a sense that Indian voters either didn’t much care about the assault on liberal democracy or mostly agreed with it. But the BJP’s surprising underperformance suggests otherwise.

The Hindu, a leading Indian newspaper, published an essential post-election data analysis breaking down what we know about the results. One of the more striking findings is that the opposition parties surged in parliamentary seats reserved for members of “scheduled castes” — the legal term for Dalits, the lowest caste grouping in the Hindu hierarchy.

Caste has long been an essential cleavage in Indian politics, with Dalits typically favoring the left-wing Congress party over the BJP (long seen as an upper-caste party). Under Modi, the BJP had seemingly tamped down on the salience of class by elevating all Hindus — including Dalits — over Muslims. Yet now it’s looking like Dalits were flocking back to Congress and its allies. Why?

According to experts, Dalit voters feared the consequences of a BJP landslide. If Modi’s party achieved its 400-seat target, they’d have more than enough votes to amend India’s constitution. Since the constitution contains several protections designed to promote Dalit equality — including a first-in-the-world affirmative action system — that seemed like a serious threat to the community. It seems, at least based on preliminary data, that they voted accordingly.

The Dalit vote is but one example of the ways in which Modi’s brazen willingness to assail Indian institutions likely alienated voters.

Uttar Pradesh (UP), India’s largest and most electorally important state, was the site of a major BJP anti-Muslim campaign. It unofficially kicked off its campaign in the UP city of Ayodhya earlier this year, during a ceremony celebrating one of Modi’s crowning achievements: the construction of a Hindu temple on the site of a former mosque that had been torn down by Hindu nationalists in 1992.

Yet not only did the BJP lose UP, it specifically lost the constituency — the city of Faizabad — in which the Ayodhya temple is located. It’s as direct an electoral rebuke to BJP ideology as one can imagine.

In Maharashtra, the second largest state, the BJP made a tactical alliance with a local politician, Ajit Pawar, facing serious corruption charges. Voters seemingly punished Modi’s party for turning a blind eye to Pawar’s offenses against the public trust. Across the country, Muslim voters turned out for the opposition to defend their rights against Modi’s attacks.

The global lesson here is clear: Even popular authoritarians can overreach.

By turning “400 seats” into a campaign slogan, an all-but-open signal that he intended to remake the Indian state in his illiberal image, Modi practically rang an alarm bell for constituencies worried about the consequences. So they turned out to stop him en masse.

The BJP’s electoral underperformance is, in no small part, the direct result of their leader’s zealotry going too far.

Return of the Gandhis?

Of course, Modi’s mistakes might not have mattered had his rivals failed to capitalize. The Indian opposition, however, was far more effective than most observers anticipated.

Perhaps most importantly, the many opposition parties coordinated with each other. Forming a united bloc called INDIA (Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance), they worked to make sure they weren’t stealing votes from each other in critical constituencies, positioning INDIA coalition candidates to win straight fights against BJP rivals.

The leading party in the opposition bloc — Congress — was also more put together than people thought. Its most prominent leader, Rahul Gandhi, was widely dismissed as a dilettante nepo baby: a pale imitation of his father Rajiv and grandmother Indira, both former Congress prime ministers. Now his critics are rethinking things.

“I owe Rahul Gandhi an apology because I seriously underestimated him,” says Manjari Miller, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Miller singled out Gandhi’s yatras (marches) across India as a particularly canny tactic. These physically grueling voyages across the length and breadth of India showed that he wasn’t just a privileged son of Indian political royalty, but a politician willing to take risks and meet ordinary Indians where they were. During the yatras, he would meet directly with voters from marginalized groups and rail against Modi’s politics of hate.

“The persona he’s developed — as somebody kind, caring, inclusive, [and] resolute in the face of bullying — has really worked and captured the imagination of younger India,” says Suryanarayan. “If you’ve spent any time on Instagram Reels, [you’ll see] an entire generation now waking up to Rahul Gandhi’s very appealing videos.”

This, too, has a lesson for the rest of the world: Tactical innovation from the opposition matters even in an unfair electoral context.

There is no doubt that, in the past 10 years, the BJP stacked the political deck against its opponents. They consolidated control over large chunks of the national media, changed campaign finance law to favor themselves, suborned the famously independent Indian Electoral Commission, and even intimidated the Supreme Court into letting them get away with it.

The opposition, though, managed to find ways to compete even under unfair circumstances. Strategic coordination between them helped consolidate resources and ameliorate the BJP cash advantage. Direct voter outreach like the yatra helped circumvent BJP dominance in the national media.

To be clear, the opposition still did not win a majority. Modi will have a third term in office, likely thanks in large part to the ways he rigged the system in his favor.

Yet there is no doubt that the opposition deserves to celebrate. Modi’s power has been constrained and the myth of his invincibility wounded, perhaps mortally. Indian voters, like those in Brazil and Poland before them, have dealt a major blow to their homegrown authoritarian faction.

And that is something worth celebrating.

YOU’VE READ 1 ARTICLE IN THE LAST MONTH

Here at Vox, we believe in helping everyone understand our complicated world, so that we can all help to shape it. Our mission is to create clear, accessible journalism to empower understanding and action.

If you share our vision, please consider supporting our work by becoming a Vox Member. Your support ensures Vox a stable, independent source of funding to underpin our journalism. If you are not ready to become a Member, even small contributions are meaningful in supporting a sustainable model for journalism.

Thank you for being part of our community.

Swati Sharma Vox Editor-in-Chief

Modi’s win in India looks a lot like a loss - Vox

Modi won the Indian election. So why does it seem like he lost?

The BJP’s poor performance shows the limits of his autocratic, Hindu supremacist policies.

by Ellen Ioanes Jun 7, 2024

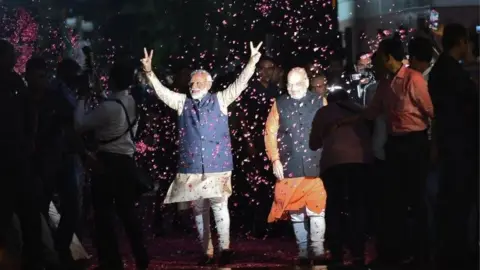

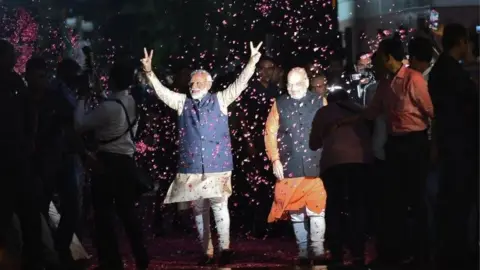

Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister, greets supporters at the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) headquarters during election results night in New Delhi, India, on June 4, 2024.

Prakash Singh/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Narendra Modi will be sworn in for his third term as India’s prime minister on Sunday after winning the post again in India’s momentous 2024 elections. But this week’s elections delivered a shocking blow to Modi’s dominance and will likely curb his autocratic tendencies.

There was never any serious doubt that Modi would remain in the top spot; he faced no credible opposition during the last two elections. And heading into this year’s six-week-long staggered election, he was widely expected to further consolidate his hold over Indian politics.

But surprisingly, he did not: Not only did Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) lose a huge number of parliamentary seats to a revitalized opposition coalition, but it also lost big in states where it has enjoyed massive popularity, including Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state. Modi campaigned on a promise to win more than 400 seats, which would have given his coalition more than enough power to amend the constitution, which requires a two-thirds majority, or 362 seats. Even though he won this year’s contest, he has for now failed in his ambition to further consolidate power.

And that has real consequences: He’ll likely face new constraints on his increasingly authoritarian leadership thanks to a renewed opposition coalition — and possibly from within his own coalition, too.

Modi is still a popular politician, but the BJP has failed to deliver on an economic front for many Indians, from farmers to young university graduates. “It seems clear that one thing that the opposition did very well was put the attention on things like unemployment and inflation,” Rohini Pande, director of the Economic Growth Center at Yale University, told Vox.

Modi has “been in power for 10 years,” Milan Vaishnav, director of the South Asia program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, told Vox. “He made some pretty lofty promises. And running on the cult of personality after 10 years is harder to do than it was the first time around or the second time around ... There’s no dominant kind of emotive issue in the ether. People are kind of asking, ‘Well, what have you done for me lately?’”

That kind of messaging — about people’s material concerns, rather than the Hindu nationalism and cult of personality that characterized the Modi and BJP campaigns — helped propel the once-dominant Congress Party, led by political scion Rahul Gandhi, and its coalition partners to surprising victories in parliament and throughout the country.

It’s too early to tell whether these elections will move the country away from the Hindutva, or the Hindu supremacist ideology that the BJP has championed; the opposition coalition is untested and could prove to be fractious and fragile. And, again, Modi still won, as evidenced by his upcoming inauguration on Sunday. But the bigger picture is that, at least for now, the Indian electorate is pushing back against his authoritarian and populist policies and re-entrenching the democratic principles, including secularism, on which its constitution is based.

To understand how big of a deal this is, look to Uttar Pradesh

The BJP’s stronghold has traditionally been in poorer northern states, like Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh (UP for short), which is India’s most populous state and has the most seats in the Lok Sabha, the equivalent of the US House of Representatives. That made the BJP’s massive loss in UP perhaps the biggest surprise of the election. Going into the contest, many experts believed there was no way Modi and his party could lose the state where it fulfilled an existential Hindu nationalist goal, constructing a temple for the god Ram on the remains of the Babri Masjid, a storied mosque destroyed by rioters in 1992. That riot, tacitly sanctioned by local authorities, boosted the profile of the BJP and led to a decades-long court fight about whether the Ram Mandir could be constructed. In the face of protests, Modi consecrated the temple earlier this year.

The BJP also lost seats in Maharashtra, the coastal state home to Mumbai — one of India’s most politically and economically important cities — as well as the agricultural states of Haryana, Rajasthan, and Punjab. Those three states have been rocked by extensive farmers’ protests which have severely damaged Modi’s credibility there.

But the party’s loss in UP is the most symbolically and politically significant of all; in terms of American politics, it would be similar to former President Donald Trump losing Texas or Florida in this year’s coming election.

“Losing UP meant that he dropped below the majority mark, majority number” of parliamentary seats in the Lok Sabha, Ashutosh Varshney, director of the Saxena Center for Contemporary South Asia at Brown University, told Vox. “The UP was critical for that.”

Inflation and lack of job creation primarily drove BJP’s losses, Paul Kenny, professor of political science at Australian Catholic University, told Vox.

“So like Trump, in a way, he really took a hit with Covid,” he said. “Inflation has really kind of gone through the roof, and employment — especially urban unemployment and youth unemployment — has also [been a] reason. So when you look at inflation of about 6 percent, and food inflation of even higher, maybe 8 percent, that really affects the poor. And inflation in particular, is a really strong indicator of incumbent reelection success, especially in developing countries.”

But there were other problems, including concerns that Muslims and people from marginalized castes had about their constitutional protections under Modi. The BJP’s tactic of silencing critics via arrests and threat

“This qualifies as a climate of fear,” Varshney said. “But the climate of fear is not such that it would stop them from going to the polling booth. No, they’ll go and vote. What it’s doing is impeding the conversation before that.” That climate of fear may have contributed to the surprise results — politicians and pollsters couldn’t predict that people would vote against the BJP because they weren’t saying so aloud.

Gandhi’s campaign filtered voters’ concerns — about the economy, their rights, and massive inequality — through the lens of the constitution. The opposition made the argument that if the BJP won a majority in the parliament, it would make unfavorable constitutional amendments, Varshney said. “In every rally — every single rally — Rahul Gandhi had a copy of the constitution in his hands.”

That concern may have driven many voters from marginalized castes away from the BJP because they have certain rights and protections under the constitution. Groups like the Dalits, OBCs (Other Backwards Castes), and Scheduled Tribes — typically, though not always, still part of India’s Hindu majority — had been socially oppressed and suffered from a lack of educational and job opportunities, as well as political representation. India’s democratic constitution guarantees a measure of rights and opportunities, including representation quotas in politics, for these groups. Though the BJP had previously managed to unite Hindus as a political bloc across castes with its Hindutva policies, the opposition exploitation of caste politics may have had a significant impact in UP.

After 10 years, Modi will face some constraints on his rule

Overall, the BJP lost 63 of the seats it previously held in the Lok Sabha. That means that, although the BJP still has the most seats of any party in the lower house of parliament, it doesn’t have a majority. Together with its coalition partners, the BJP still has a 293-seat majority, but that’s not enough to make constitutional amendments unchallenged. Modi and the BJP will now encounter more friction — both from the opposition and potentially from within the coalition it formed as an insurance policy during the campaign.

The BJP campaigned in coalition with two regional secular parties, the Telugu Desam Party (TDP) and Janata Dal (United), or JDU, forming the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) party. How they will govern together under Modi, however, remains to be seen.

The leadership of the TDP and JDU parties don’t see eye to eye with Modi on some fairly important issues. Nitish Kumar of the JDU party wants to conduct a caste census across the country (something the opposition INDIA coalition has also advocated for) which would give the government a better idea of how to distribute resources, programs, and political representation for marginalized castes especially. But that turn to caste politics threatens Modi’s message of cross-caste Hindu solidarity against other groups. The TDP leadership has also promised to reserve protections and rights for Muslims in the states of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh — something that Modi previously promised to abolish.

That could make the NDA coalition fragile, and Modi’s desire to remain in power gives a fair amount of leverage to JDU and TDP to extract demands for their states from the central government.

“Modi now will go back to having to depend on a lot of regional partners and state parties,” Kenny said. “And the BJP, even at its height of Modi’s ability to bring in votes with charisma, was still dependent on buying the support of smaller coalitions — so being able to dispense goods, to dispense patronage, to effectively buy votes by distributing. Whether it’s things [like] rations and fuel support, and all of these kinds of things that go on in daily politics in India. That’s just come back to the fore.”

Furthermore, because there is now a fulsome opposition party, “the parliament will once again become a site for vigorous debate and contestation,” Varshney said. The BJP will not be able to push through laws as they did with recent criminal code reforms without debate.

But the opposition coalition is untested, and could become fractious over time, too, Vaishnav said. “These are parties which have been at each other’s throats, and who are highly competitive with one another in states where they have a real presence. And they’ve managed to let bygones be bygones, for the purposes of fighting this election. But when the electoral spotlight is off, will they be able to continue this method of collaboration and cooperation [having] achieved the short-term objective?”

This election, while pivotal, is far from the end of the BJP or Modi, Vaishnav said. “[Modi] is an incredibly crafty savvy marketer and politician who has an incredible amount of charisma and a reservoir of goodwill amongst the people.”

Populist and personality-driven politics are trending upward all around the world, partly because of a decline in traditional political parties and the institutions that support them, Kenny said. Modi’s just part of that wave. But this year’s election demonstrated that the trend toward populism and authoritarianism — in democratic societies, anyway — has its limits.

Here at Vox, we believe in helping everyone understand our complicated world, so that we can all help to shape it. Our mission is to create clear, accessible journalism to empower understanding and action.

If you share our vision, please consider supporting our work by becoming a Vox Member. Your support ensures Vox a stable, independent source of funding to underpin our journalism. If you are not ready to become a Member, even small contributions are meaningful in supporting a sustainable model for journalism.

Thank you for being part of our community.

Swati Sharmam Vox Editor-in-Chie

What went wrong for Modi? - Asia News Network - Asia News Network

https://asianews.network/what-

MenuMenu

What went wrong for Modi?

Modi faces significant challenges in his third term as he leads a coalition government for the first time since 2014. With his BJP falling short of a majority, Modi must rely on key allies like the Janata Dal (United) and Telugu Desam Party.

Ivanpal Singh Grewal

The Star

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi

June 12, 2024

KUALA LUMPUR – AS A close and interested observer of Indian politics, I watched the marathon election campaign unfold with much interest.

I shared the popular sentiment and opinion that the Indian Prime Minister will lead his party and coalition back to power with a thumping majority. But the vagaries of Indian politics exhibited its full muscle and threw up a surprising verdict.

Modi’s BJP failed to secure an outright majority in the recent election due to several factors. A significant drop in seats, particularly in Uttar Pradesh, was a major setback. The state’s loss was pivotal as it holds substantial sway in national politics.

Rising joblessness, increasing prices, and growing inequality contributed to voter dissatisfaction. Additionally, a controversial army recruitment reform and Modi’s divisive campaign targeting Muslims alienated some voters.

The opposition Congress Party-led INDIA alliance made a surprising comeback, defying earlier predictions of its decline. Rahul Gandhi led a spirited campaign that resonated with many voters. The revival of coalition politics marked a return to “normal politics,” with multiple parties sharing and competing for power. The BJP, once seen as all-powerful, now relies on coalition partners, making it vulnerable to potential collapse if allies feel neglected.

Modi’s personal brand has also taken a hit. Despite his stable governance record, efficient welfare programs, and enhancing India’s global image, anti-incumbency sentiments affected his popularity. His ambitious campaign slogan aiming for more than 400 seats may have backfired, raising fears of constitutional changes among poorer voters and backward caste voters who felt Modi may amend the constitution to remove reservation they enjoy. This election result shows that even charismatic leaders like Modi are not invincible.

The BJP’s loss of seats has provided renewed hope to the opposition. The Congress-led alliance’s resurgence signifies a potential shift in Indian politics, challenging the one-party dominant system that characterised Modi’s decade-long reign. Upcoming state elections in Maharashtra, Jharkhand, Haryana, and Delhi could further challenge the BJP, offering more opportunities for regional parties to gain influence.

There is saying that good economics is good politics.

During Modi’s tenure, India’s economic indicators and infrastructure development have seen notable improvements. India’s GDP growth averaged around 7% from 2014 to 2019, positioning it as one of the fastest-growing major economies globally. Correspondingly, GDP per capita increased from approximately $1,600 in 2014 to around $2,000 in 2023, reflecting a rise in overall economic prosperity. Efforts to reduce poverty also showed progress, with the poverty headcount ratio at $1.90 a day (2011 PPP) decreasing from 21.2% in 2011 to an estimated 10% in 2019, although the Covid-19 pandemic impacted further advancements.

Infrastructure development has been a cornerstone of Modi’s economic agenda. The National Highways Authority of India (NHAI) constructed approximately 37,000km of national highways from 2014 to 2023, significantly improving connectivity and boosting economic activity. Under the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan (Clean India Mission), over 100 million toilets were built between 2014 and 2019, contributing to India being declared open defecation free (ODF) in October 2019. The Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (Prime Minister’s Housing Scheme) targeted the construction of 20 million urban homes and 30 million rural homes by 2022, with around 10 million urban homes and 22 million rural homes completed by 2023, addressing the housing needs of the urban and rural poor.

Additionally, the Saubhagya scheme aimed at universal household electrification achieved significant success, with almost 100% of households electrified by 2019. The Jan Dhan Yojana initiative led to the opening of over 400 million bank accounts for previously unbanked individuals, promoting financial inclusion and economic participation. These metrics highlight the substantial economic and infrastructural progress made under Prime Minister Modi’s administration, contributing to improved living standards and sustained economic development in India.

However, all of this was not enough to win Modi’s a 3rd term on his own. Modi faces significant challenges in his third term as he leads a coalition government for the first time since 2014. With his BJP falling short of a majority, Modi must rely on key allies like the Janata Dal (United) and Telugu Desam Party (TDP), led by veteran politicians Nitish Kumar and N Chandrababu Naidu. These leaders have previously served in BJP-led coalitions but have also parted ways over disagreements, indicating potential instability. Modi’s historically domineering style may need to adapt to a more consultative approach to maintain coalition harmony and prevent collapse.

But all is also not last because some commentators argue that coalition governance could bring about a healthier democratic process in India, potentially reducing Modi’s dominance and decentralizing power. It may also increase checks and balances, embolden the opposition, and make institutions like the judiciary, bureaucracy, and media more independent. However, Modi’s coalition differs from past ones, as the BJP remains a dominant force with 240 seats. Successful coalition politics will demand Modi’s ability to collaborate and accommodate the demands of his allies, which include state-specific issues and influential ministry positions.

Also, Modi must address the concerns of the voters who feel left out and divorced from India’s economic boom. Modi’s government will need to address significant structural reforms in agriculture, land, and labor to boost job creation and incomes for the poor and middle class.

The coalition will also have to navigate contentious issues like simultaneous federal and state elections, the Uniform Civil Code, and the redrawing of parliamentary boundaries. Whether Modi can transform into a more consensual leader remains uncertain. Successful politicians often reinvent themselves, and Modi’s ability to adapt will be crucial in determining the success of his third term amid coalition dynamics.

But those who have previously written off Modi had to eat humble pie as he is a greater learner, and he has bounced back from previous setbacks very well.

At the same time the INDIA bloc will also have to show its wherewithal and deal with its own polarities. For sure, Indian politics will remain interesting and engaging.

Modi won the Indian election. So why does it seem like he lost?

The BJP’s poor performance shows the limits of his autocratic, Hindu supremacist policies.

Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister, greets supporters at the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) headquarters during election results night in New Delhi, India, on June 4, 2024.

Prakash Singh/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Narendra Modi will be sworn in for his third term as India’s prime minister on Sunday after winning the post again in India’s momentous 2024 elections. But this week’s elections delivered a shocking blow to Modi’s dominance and will likely curb his autocratic tendencies.

There was never any serious doubt that Modi would remain in the top spot; he faced no credible opposition during the last two elections. And heading into this year’s six-week-long staggered election, he was widely expected to further consolidate his hold over Indian politics.

But surprisingly, he did not: Not only did Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) lose a huge number of parliamentary seats to a revitalized opposition coalition, but it also lost big in states where it has enjoyed massive popularity, including Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state. Modi campaigned on a promise to win more than 400 seats, which would have given his coalition more than enough power to amend the constitution, which requires a two-thirds majority, or 362 seats. Even though he won this year’s contest, he has for now failed in his ambition to further consolidate power.

And that has real consequences: He’ll likely face new constraints on his increasingly authoritarian leadership thanks to a renewed opposition coalition — and possibly from within his own coalition, too.

Modi is still a popular politician, but the BJP has failed to deliver on an economic front for many Indians, from farmers to young university graduates. “It seems clear that one thing that the opposition did very well was put the attention on things like unemployment and inflation,” Rohini Pande, director of the Economic Growth Center at Yale University, told Vox.

Modi has “been in power for 10 years,” Milan Vaishnav, director of the South Asia program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, told Vox. “He made some pretty lofty promises. And running on the cult of personality after 10 years is harder to do than it was the first time around or the second time around ... There’s no dominant kind of emotive issue in the ether. People are kind of asking, ‘Well, what have you done for me lately?’”

That kind of messaging — about people’s material concerns, rather than the Hindu nationalism and cult of personality that characterized the Modi and BJP campaigns — helped propel the once-dominant Congress Party, led by political scion Rahul Gandhi, and its coalition partners to surprising victories in parliament and throughout the country.

It’s too early to tell whether these elections will move the country away from the Hindutva, or the Hindu supremacist ideology that the BJP has championed; the opposition coalition is untested and could prove to be fractious and fragile. And, again, Modi still won, as evidenced by his upcoming inauguration on Sunday. But the bigger picture is that, at least for now, the Indian electorate is pushing back against his authoritarian and populist policies and re-entrenching the democratic principles, including secularism, on which its constitution is based.

To understand how big of a deal this is, look to Uttar Pradesh

The BJP’s stronghold has traditionally been in poorer northern states, like Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh (UP for short), which is India’s most populous state and has the most seats in the Lok Sabha, the equivalent of the US House of Representatives. That made the BJP’s massive loss in UP perhaps the biggest surprise of the election. Going into the contest, many experts believed there was no way Modi and his party could lose the state where it fulfilled an existential Hindu nationalist goal, constructing a temple for the god Ram on the remains of the Babri Masjid, a storied mosque destroyed by rioters in 1992. That riot, tacitly sanctioned by local authorities, boosted the profile of the BJP and led to a decades-long court fight about whether the Ram Mandir could be constructed. In the face of protests, Modi consecrated the temple earlier this year.

The BJP also lost seats in Maharashtra, the coastal state home to Mumbai — one of India’s most politically and economically important cities — as well as the agricultural states of Haryana, Rajasthan, and Punjab. Those three states have been rocked by extensive farmers’ protests which have severely damaged Modi’s credibility there.

But the party’s loss in UP is the most symbolically and politically significant of all; in terms of American politics, it would be similar to former President Donald Trump losing Texas or Florida in this year’s coming election.

“Losing UP meant that he dropped below the majority mark, majority number” of parliamentary seats in the Lok Sabha, Ashutosh Varshney, director of the Saxena Center for Contemporary South Asia at Brown University, told Vox. “The UP was critical for that.”

Inflation and lack of job creation primarily drove BJP’s losses, Paul Kenny, professor of political science at Australian Catholic University, told Vox.

“So like Trump, in a way, he really took a hit with Covid,” he said. “Inflation has really kind of gone through the roof, and employment — especially urban unemployment and youth unemployment — has also [been a] reason. So when you look at inflation of about 6 percent, and food inflation of even higher, maybe 8 percent, that really affects the poor. And inflation in particular, is a really strong indicator of incumbent reelection success, especially in developing countries.”

But there were other problems, including concerns that Muslims and people from marginalized castes had about their constitutional protections under Modi. The BJP’s tactic of silencing critics via arrests and threats may have begun to wear on people, though it’s not clear how much that influenced their choices in the polling booth.

“This qualifies as a climate of fear,” Varshney said. “But the climate of fear is not such that it would stop them from going to the polling booth. No, they’ll go and vote. What it’s doing is impeding the conversation before that.” That climate of fear may have contributed to the surprise results — politicians and pollsters couldn’t predict that people would vote against the BJP because they weren’t saying so aloud.

Gandhi’s campaign filtered voters’ concerns — about the economy, their rights, and massive inequality — through the lens of the constitution. The opposition made the argument that if the BJP won a majority in the parliament, it would make unfavorable constitutional amendments, Varshney said. “In every rally — every single rally — Rahul Gandhi had a copy of the constitution in his hands.”

That concern may have driven many voters from marginalized castes away from the BJP because they have certain rights and protections under the constitution. Groups like the Dalits, OBCs (Other Backwards Castes), and Scheduled Tribes — typically, though not always, still part of India’s Hindu majority — had been socially oppressed and suffered from a lack of educational and job opportunities, as well as political representation. India’s democratic constitution guarantees a measure of rights and opportunities, including representation quotas in politics, for these groups. Though the BJP had previously managed to unite Hindus as a political bloc across castes with its Hindutva policies, the opposition exploitation of caste politics may have had a significant impact in UP.

After 10 years, Modi will face some constraints on his rule

Overall, the BJP lost 63 of the seats it previously held in the Lok Sabha. That means that, although the BJP still has the most seats of any party in the lower house of parliament, it doesn’t have a majority. Together with its coalition partners, the BJP still has a 293-seat majority, but that’s not enough to make constitutional amendments unchallenged. Modi and the BJP will now encounter more friction — both from the opposition and potentially from within the coalition it formed as an insurance policy during the campaign.

The BJP campaigned in coalition with two regional secular parties, the Telugu Desam Party (TDP) and Janata Dal (United), or JDU, forming the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) party. How they will govern together under Modi, however, remains to be seen.

The leadership of the TDP and JDU parties don’t see eye to eye with Modi on some fairly important issues. Nitish Kumar of the JDU party wants to conduct a caste census across the country (something the opposition INDIA coalition has also advocated for) which would give the government a better idea of how to distribute resources, programs, and political representation for marginalized castes especially. But that turn to caste politics threatens Modi’s message of cross-caste Hindu solidarity against other groups. The TDP leadership has also promised to reserve protections and rights for Muslims in the states of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh — something that Modi previously promised to abolish.

That could make the NDA coalition fragile, and Modi’s desire to remain in power gives a fair amount of leverage to JDU and TDP to extract demands for their states from the central government.

“Modi now will go back to having to depend on a lot of regional partners and state parties,” Kenny said. “And the BJP, even at its height of Modi’s ability to bring in votes with charisma, was still dependent on buying the support of smaller coalitions — so being able to dispense goods, to dispense patronage, to effectively buy votes by distributing. Whether it’s things [like] rations and fuel support, and all of these kinds of things that go on in daily politics in India. That’s just come back to the fore.”

Furthermore, because there is now a fulsome opposition party, “the parliament will once again become a site for vigorous debate and contestation,” Varshney said. The BJP will not be able to push through laws as they did with recent criminal code reforms without debate.

But the opposition coalition is untested, and could become fractious over time, too, Vaishnav said. “These are parties which have been at each other’s throats, and who are highly competitive with one another in states where they have a real presence. And they’ve managed to let bygones be bygones, for the purposes of fighting this election. But when the electoral spotlight is off, will they be able to continue this method of collaboration and cooperation [having] achieved the short-term objective?”

This election, while pivotal, is far from the end of the BJP or Modi, Vaishnav said. “[Modi] is an incredibly crafty savvy marketer and politician who has an incredible amount of charisma and a reservoir of goodwill amongst the people.”

Populist and personality-driven politics are trending upward all around the world, partly because of a decline in traditional political parties and the institutions that support them, Kenny said. Modi’s just part of that wave. But this year’s election demonstrated that the trend toward populism and authoritarianism — in democratic societies, anyway — has its limits.

India’s election shows the world’s largest democracy is still a democracy

The biggest takeaways from Narendra Modi's political setback.

If the basic test of whether a country remains a democracy is that the party in power can still suffer a setback at the ballot box, India passed on Tuesday. Results from the nation’s parliamentary elections — the largest in the world — indicate a shocking electoral setback for Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

“Setback,” to be clear, is a relative term here. At the end of the staggered six-week election, Modi will become only the second Indian prime minister to win a third consecutive term. As of this writing, the BJP-led National Democracy Alliance (NDA) has won 289 seats in the 543-seat parliament and is leading in one more. A majority requires 272 seats.

The BJP itself has won 240 seats. That’s more than any Indian party won between 1984 and 2009, when Modi first came to power, and in most elections, it would have been an amazing result. But the expectations game is real, and Modi and his party lost it.

During the campaign, the NDA had a stated goal of winning 400 seats: a supermajority that would have allowed them to push through major legislative and constitutional changes. They didn’t come close. And after winning an absolute majority on its own in the last election, the BJP will likely now have to rely on its smaller coalition partners in the NDA to form a government.

Exit polls over the weekend were also wildly wrong, with most incorrectly projecting around a 350-seat victory for Modi. (One of the more bizarre media moments on Tuesday was a prominent pollster breaking down in tears on Indian TV over his erroneous forecast and being comforted by his fellow panelists on camera. Not something you’re likely to see from Frank Luntz.)

The opposition Congress Party, which very recently looked headed for political oblivion under the leadership of Rahul Gandhi, the much-mocked fourth-generation scion of India’s most prominent political dynasty, appears likely to double its tally from the last election.

It’s far too soon to say it’s the end or even the beginning of the end for Modi and the BJP, but they’re facing something they haven’t in quite some time: meaningful opposition and uncertainty. And the world’s biggest electorate showed it’s still capable of surprise and independence.

How Modi messed up

So what went wrong for Modi? In a country of 1.4 billion people, there could easily be that many reasons, and it’s still too early to make sweeping statements. But the growing consensus seems to be that India’s economy and pocketbook issues took precedence for many voters over the BJP’s avowedly religious and ideological project.

While India has seen rapid GDP growth and infrastructure investment during the Modi years, unemployment has remained stubbornly high and, in many parts of the country, wage growth has been static.

The ruling party’s most significant losses came in Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state and a longtime BJP bastion. The most symbolically significant seat lost may be in Ayodhya, where earlier this year Modi presided over the opening of the Ram Mandir, a massive and controversial new Hindu temple built on the site of a historic mosque torn down by a Hindu nationalist mob in 1992.