What Is The Rule of Law

WhatIsTheRuleOfLaw

https://www.ruleoflaw.org.au/

What is the Rule of Law?

WSJ Wall Street Journal - WSJ Wall Street Journal November2023 (inltv.co.uk)

Handy Easy Email and World News Links WebMail

GoogleSearch INLTV.co.uk Y

USAMAIL W

Bahai.org AustralianDai

No One Is Above The Law

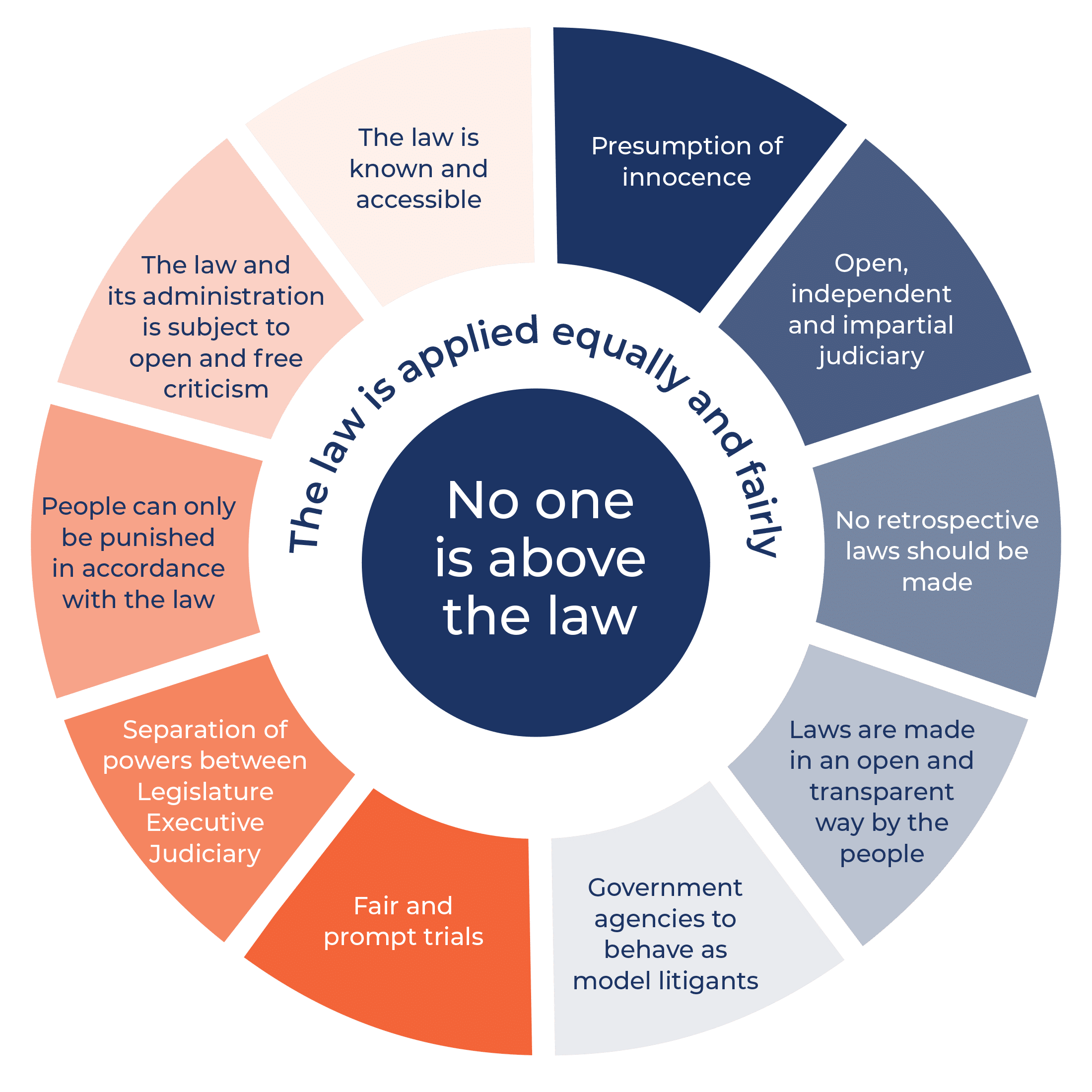

The Wheel of the Law

https://www.ruleoflaw.org.au/

At its most basic level the rule of law is the concept that both the government and citizens know the law and obey it.

A good definition of the rule of law that has near universal acceptance states

“…most of the content of the rule of law can be summed up in two points:

(1) that the people (including, one should add, the government) should be ruled by the law and obey it and(2) that the law should be such that people will be able (and, one should add, willing) to be guided by it.”

Approaches to the Rule of Law

The rule of law is a complex concept that has been debated and analysed by scholars for centuries. At its core, the rule of law is concerned with the fairness, accessibility, and efficiency of the legal system, from the creation of laws, through their enforcement, and finally to the court process.

It encompasses concerns about equality under the law, government accountability, constraints on arbitrary power, independent and impartial dispute resolution, protection of human rights, democratic involvement in law-making, and a broader culture of lawfulness.

This section explores four different approaches to the rule of law:

- A. V. Dicey, a famous nineteenth-century English legal theorist;

- Lord Bingham, a senior British judge who died in 2010;

- Professor Martin Krygier, an Australian legal theorist;

- Rule of Law Education Centre Rule of Law Wheel

There are also many other lawyers and scholars who also discuss the rule of law, including Joseph Raz, Lon Fuller, F. A. Hayek, Philip Selznick, Brian Tamanaha, Geoffrey de Q. Walker, and James Spigelman.

A.V Dicey

Albert Venn Dicey was a nineteenth-century English legal theorist. He is the most famous rule of law theorist, although his interpretation of the concept has been criticised.

Dicey argued that England displayed the rule of law in three ways:

-

- “That no man is punishable, or can be lawfully made to suffer in body or goods, except for a distinct breach of law established in the ordinary legal manner before the ordinary Courts of the land. In this sense, the rule of law is contrasted with every system of government based on the exercise by persons in authority of wide, arbitrary, or discretionary powers of constraint;”

- “Not only that with us no man is above the law, but (what is a different thing) that here every man, whatever be his rank or condition, is subject to the ordinary law of the realm and amenable to the jurisdiction of the ordinary tribunals;” and

- “That the general principles of the constitution (as, for example, the right to personal liberty, or the right of public meeting) are with us the result of judicial decisions determining the rights of private persons in particular cases brought before the Courts; whereas, under many foreign constitutions, the security (such as it is) given to the rights of individuals results, or appears to result, from the general principles of the constitution.”

Dicey’s interpretation of the rule of law has long been criticised as focusing too much on England, to the exclusion of other countries. It is no longer true, say his critics, if indeed it ever was, that England is the only country governed by the rule of law. The rest of the Western world, such as Continental Europe and the United States, not to mention non-Western countries, cannot have the rule of law, according to Dicey’s interpretation, simply because they are not English. Therefore, his interpretation is flawed.

Nevertheless, it highlights some key principles that have remained important throughout later discussions of the rule of law: a distrust of arbitrary power, and an insistence on equality before the law.

Although flawed, Dicey’s account of the rule of law in England shaped future generations of lawyers and scholars, and raised some key principles that are still held to be important today.

Lord Bingham

Lord Tom Bingham was a British judge who died in 2010. He was Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, and Master of the Rolls, and Senior Law Lord. He published a book called The Rule of Law in 2010, which sets out eight principles that Lord Bingham considered made up the rule of law:

-

- “The law must be accessible and, so far as possible, intelligible, clear, and predictable”;

- “Questions of legal right and liability should ordinarily be resolved by application of the law, and not the exercise of discretion”;

- “The laws of the land should apply equally to all, save to the extent that objective differences justify differentiation”;

- “Legal protection of such human rights as, within that society, are seen as fundamental”;

- “Means must be provided for resolving, without prohibitive cost or inordinate delay, bona fide civil disputes which the parties themselves are unable to resolve”;

- “Ministers and public officers at all levels must exercise the powers conferred on them reasonably, in good faith, for the purpose for which the powers were conferred, and without exceeding the limits of such powers”;

- “The adjudicative procedures provided by the state should be fair”; and

- “Compliance by the state with its obligations in international law.”

Bingham’s approach is more helpful than Dicey’s in many ways, drawing attention to the principles that countries around the world might aspire to, regardless of their history or arrangement of government institutions. There is nothing specifically English about his definition of the rule of law.

Nevertheless, Bingham’s broad definition is also controversial, particularly in its inclusion of human rights protections, and compliance with international law. Critics have argued that it reads more like a shopping list of ideal characteristics of a country or government, rather than an explanation of the rule of law. This, they say, robs the concept of ‘the rule of law’ of any meaningful content; it just becomes a list of things we think are good for a government to do.

Profesor Martin Krygier

Professor Martin Krygier, a former member of the governing committee of the Rule of Law Institute, is an Australian legal theorist. He is currently the Gordon Samuels Professor Law and Social Theory at the University of New South Wales, in Sydney.

Krygier’s interpretation of the rule of law differs from many other scholars in his insistence that we should not list principles or institutions that we regard as indispensable to the rule of law, but rather first ask why we value the rule of law – what is the purpose of it – and then proceed to identify the institutions and legal mechanisms that will advance that purpose.

Krygier argues that the purpose of the rule of law is “to temper or moderate the exercise of power, in order to avoid its arbitrary use”. Therefore, institutions or mechanisms that advance this purpose in a particular society or point in time are what we mean by the rule of law.

Rule of Law Education Centre

The Rule of Law Education Centre uses the Rule of Law Wheel to start discussion about the question “What is the Rule of Law?”

Central to the wheel and the rule of law is the concept that no one is above the law – it is applied equally and fairly to both the government and citizens. This means that all people, regardless of their status, race, culture, religion, or any other attribute, should be ruled equally by just laws.

Beyond this, the outer edge of the wheel illustrates the number of inter-related principles that uphold the rule of law in Australia, such as the presumption of innocence, and fair and prompt trials. These principles can be considered essential elements that contribute to maintaining the rule of law. Without these, the wheel would fail to turn and Australia’s rule of law would not continue to be upheld and maintained.

The final essential element is that these principles and Australia’s rule of law is supported by informed and active citizens. Without responsible and engaged citizens, society is unable to work together to uphold important principles and values which support our rule of law and democratic society.

Below is an interactive wheel, where further details on each principles can be accessed by clicking on the different sections.

Why is the Rule of Law Important for Society?

The rule of law is important because a country that adheres to the rule of law results in a society in which:

- All persons and organisations including the government are subject to and accountable to the law

- The law is known and accessible

- The Court system is independent and resolves disputes in an open and impartial manner

- All persons are presumed innocent until proven otherwise by a Court

- All persons have the right to a fair and prompt trial

- No person should be arbitrarily arrested, imprisoned, or deprived of their property

- Punishment is determined by a Court and people can only be punished in accordance with the law.

As a result, it can be said that the Rule of Law is more than simply the government and citizens knowing and obeying the law. The Rule of Law involves other ideals, for example that citizens remain active and informed and participate in the creation of just laws which regulate their behaviour and protect human rights.

At its heart, the Rule of Law is an ideal or an aspiration, that members of a society must continuously work towards.

The rule of law is essential in maintaining a free, democratic and fair society.

The Rule of Law Wheel

The relevance of the rule of law, and an understanding

of its concepts, has its origins in the Magna Carta and the Rule of Law Education Centre uses the Rule of Law Wheel to start discussion about the question “What is the Rule of Law?”

Principles of the Rule of Law

The rule of law is best described as:

‘the people (including, one should add, the government) should be ruled by the law and obey it and that the law should be such that people will be able (and, one should add, willing) to be guided by it.’

– Geoffrey de Q. Walker, The rule of law: foundation of constitutional democracy, (1st Ed., 1988).

The relevance of the rule of law is demonstrated by application of the following principles in practice:

- The law is applied equally and fairly, so that no one is above the law.

- The separation of powers between the legislature, the executive and the judiciary.

- The judicial system is independent and impartial with open justice

- The law is made by representatives of the people in an open and transparent way.

- The law is capable of being known by everyone, so that everyone can comply.

- People can only be punished in accordance with the law

- No one is subject adversely to a retrospective change of the law or prosecuted, for any offence not known to the law when committed.

- Government agencies to act as model litigants

- A fair and prompt trial.

- All people are presumed to be innocent until proven otherwise and are entitled to remain silent and are not required to incriminate themselves.

- The law and its administration is subject to open and free criticism by the people, who may assemble without fear.

‘The rule of law is an overarching principle which ensures that Australians are governed by laws which their elected representatives make and which reflect the rule of law. It requires that the laws are administered justly and fairly.’

– Robin Speed, Founder, Rule of Law Education Centre

There have been other approaches and definitions of the rule of law such as Dicey’s three principles of the rule of law and Lord Bingham’s eight principles. These can be seen on our page on Rule of Law Approaches.

The Rule of Law Wheel

To inspire discussion of the Rule of Law in practice, we use our Rule of Law Wheel which provides a way to imagine the principles and legal traditions that contribute to maintaining the rule of law in Australia.

Click on each section of the wheel below to learn more about the different principles of the rule of law:

What is the Rule of Law?

At its most basic level the rule of law is the concept that both the government and citizens know the law and obey it.

A good definition of the rule of law that has near universal acceptance states

“…most of the content of the rule of law can be summed up in two points:

(1) that the people (including, one should add, the government) should be ruled by the law and obey it and(2) that the law should be such that people will be able (and, one should add, willing) to be guided by it.”

The Rule of Law Wheel

The relevance of the rule of law, and an understanding of its concepts, has its origins in the Magna Carta and the Rule of Law Education Centre uses the Rule of Law Wheel to start discussion about the question “What is the Rule of Law?”

Central to the wheel and the rule of law is the concept that no one is above the law – it is applied equally and fairly to both the government and citizens. This means that all people, regardless of their status, race, culture, religion, or any other attribute, should be ruled equally by just laws.

Beyond this, the outer edge of the wheel illustrates a number of interrelated principles that reflect the rule of law in Australia, such as the presumption of innocence, and fair and prompt trials.

These principles can be considered essential elements that contribute to maintaining the rule of law. Without these, the wheel would fail to turn and Australia’s rule of law would not continue to be upheld and maintained.

Another essential element is that these principles and Australia’s rule of law is supported by informed and active citizens. Without responsible and engaged citizens, society is unable to work together to uphold important principles and values which support our rule of law and democratic society.

Judge Culver of the District Court of NSW outlines the essential features of the rule of law.

Her Honour then illustrates the rule of law in action with a fictional case of someone being given a package by a stranger and the differing treatment by the police and courts depending if the rule of law is alive and well.

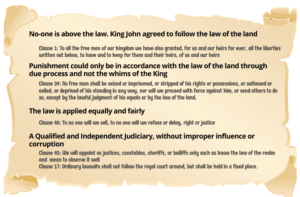

The Magna Carta established the rule of law and the idea that all citizens, including those in power, should be fairly and equally ruled by the law.

The Magna Carta ensured the King is no longer above the law, people are ruled by the law and the law alone, there is a qualified Independent Judiciary, confidence in Fair Process and the law is known by all.

Why is the Rule of Law Important for Society?

The rule of law is important because a country that adheres to the rule of law results in a society in which:

- All persons and organisations including the government are subject to and accountable to the law

- The law is known and accessible

- The Court system is independent and resolves disputes in an open and impartial manner

- All persons are presumed innocent until proven otherwise by a Court

- All persons have the right to a fair and prompt trial

- No person should be arbitrarily arrested, imprisoned, or deprived of their property

- Punishment is determined by a Court and people can only be punished in accordance with the law.

As a result, it can be said that the Rule of Law is more than simply the government and citizens knowing and obeying the law. The Rule of Law involves other ideals, for example that citizens remain active and informed and participate in the creation of just laws which regulate their behaviour and protect human rights.

At its heart, the Rule of Law is an ideal or an aspiration, that members of a society must continuously work towards.

The rule of law is essential in maintaining a free, democratic and fair society.

Rule of Law Video

This video introduces the concept of the rule of law and provides some examples of ways in which the concept supports fairness and certainty in the legal system.

Lecture Series with Kevin Lindgren AM QC

The Hon Kevin Lindgren, former Justice of the Federal Court of Australia, was appointed Adjunct Professor of the rule of law at the University of Sydney in 2012. He has lectured extensively on the concept of the rule of law and has produced a paper entitled ‘The Rule of Law: Its State of Health in Australia‘.

Professor Lindgren’s other lectures include:

https://www.ruleoflaw.org.au/principles/equality-before-the-law/

No One is Above the Law

At its most basic level, the rule of law is the concept that both the government and citizens know the law and obey it.

The phrase ‘equality before the law’ is often used in relation to the rule of law and means:

the law should apply to all people equally regardless of their status in society – rich or poor, young or old, regardless of their gender, race, culture, religion, or any other attribute.

No One Is Above The Law - The Law Is Applied Equality and Fairly

Equality before the law means that all human beings have the right to be treated equally before the law. They are also entitled to the equal protection of the law, which means all people have the right to be treated fairly and not be discriminated against because of their race, colour, gender, language, religion, political beliefs, status or any other unlawful reason.

Importantly, the law must be superior. All citizens must enjoy equality before the law and be subject to the laws of Australia.

This concept was outlined by Professor A.V. Dicey who described the rule of law as

1. It means . . . the absolute supremacy or predominance of regular law as opposed to the influence of arbitrary power, and excludes the existence of arbitrariness, of prerogative, or even of wide discretionary authority on the part of the government. Englishmen are ruled by the law, and by the law alone; a man may be punished for a breach of law, but he can be punished for nothing else.

2. It means equality before the law, or the equal subjection of all classes to the ordinary law of the land administered by the ordinary law courts; the ‘rule of law’ in this case excludes the idea of any exemption of officials or others from the duty of obedience to the law which governs other citizens or from the jurisdiction of the ordinary courts.

3. With us the law of the constitution, the rules which in foreign countries naturally form part of a constitutional code, are not the source but the consequence of the rights of individuals, as defined and enforced by the courts; . . . the principles of private law have . . . by the action of the courts and Parliament so extended as to determine the position of the Crown and its servants; thus the constitution is the result of the ordinary law of the land.

Origins of Equality before the Law: Principles from the Magna Carta

From the Magna Carta we have the principle that all citizens, including those in power, should be fairly and equally ruled by the law.

The Magna Carta was an important medieval document sealed in 1215 between King John of England and the Barons. King John was an evil King who heavily taxed his people, arbitrarily took their possessions, and threw them into prison for the smallest reason. The sealing of the Magna Carta was a key moment in the development of the legal principle of Equality before the law in England.

By sealing the Magna Carta, King John was agreeing to follow the laws of the land. It gave the people a mechanism to limit the power of the King and assert their rights. The Magna Carta established the concept of the rule of law where all citizens, including the King, must follow the law.

Under the rule of law, the law should apply to all people equally no matter if they are the King or a servant, if they are rich or poor.

As all people are equally subject to the law, all people must equally answer for their actions under the law and the law must be applied to each person in the same way. To ensure all people are bound by laws, there also must be equal access to the protections provided by the law through a fair trial and an independent and impartial judiciary.

The Magna Carta included provisions that ensured equality before the law such as

Equality before the Law and the principles from the Magna Carta that no-one is above the law and that laws must be applied equally and fairly, became key legal principles of the English justice system.

To learn more about the Magna Carta:

v

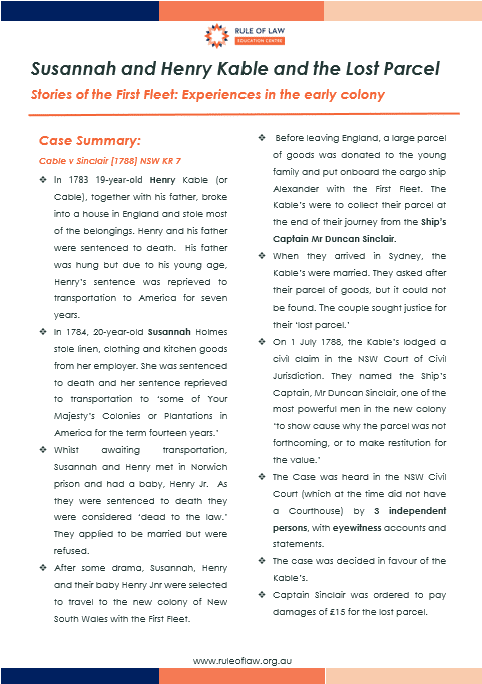

Case Study of Equality before the Law: The story of the first civil case in New South Wales, ‘The Lost Parcel’

Susannah and Henry were poor convicts who could not read or write but they were able to use the justice system to restore their loss and sue the powerful Ship’s Captain.

This case study demonstrates how the principle of equality was part of the legal system in the early colony of New South Wales and how this protected the rights of citizens, including convicts.

Further reading:

The Law of the Constitution: AV Dicey

The Rule of Law: T Bingham

https://peo.gov.au/understand-our-parliament/how-parliament-works/system-of-government/rule-of-law/

What is the Rule of Law?

At its most basic level the rule of law is the concept that both the government and citizens know the law and obey it.

A good definition of the rule of law that has near universal acceptance states

https://www.ruleoflaw.org.au/what-is-the-rule-of-law/

“…most of the content of the rule of law can be summed up in two points:

(1) that the people (including, one should add, the government) should be ruled by the law and obey it and(2) that the law should be such that people will be able (and, one should add, willing) to be guided by it.”– Geoffrey de Q. Walker, The rule of law: foundation of constitutional democracy, (1st Ed., 1988).The Rule of Law Wheel

The relevance of the rule of law, and an understanding of its concepts, has its origins in the Magna Carta and the Rule of Law Education Centre uses the Rule of Law Wheel to start discussion about the question “What is the Rule of Law?”

Central to the wheel and the rule of law is the concept that no one is above the law – it is applied equally and fairly to both the government and citizens. This means that all people, regardless of their status, race, culture, religion, or any other attribute, should be ruled equally by just laws.

Beyond this, the outer edge of the wheel illustrates a number of interrelated principles that reflect the rule of law in Australia, such as the presumption of innocence, and fair and prompt trials.

These principles can be considered essential elements that contribute to maintaining the rule of law. Without these, the wheel would fail to turn and Australia’s rule of law would not continue to be upheld and maintained.

Another essential element is that these principles and Australia’s rule of law is supported by informed and active citizens. Without responsible and engaged citizens, society is unable to work together to uphold important principles and values which support our rule of law and democratic society.

Open and Free Criticism

https://www.ruleoflaw.org.au/principles/law-and-administration-open-and-free-criticism/

This principle is underpinned by the concept of freedom of speech, which is the freedom to express and communicate one’s opinion publicly, without being punished for it.

Sometimes known as the right to freedom of opinion and expression, people have the right to hold opinions without interference. This extends to any medium, including written and oral communication, public protest and the media.

Freedom of speech is important to the rule of law as the laws are made by the people (through their representatives). As the laws are made and administered on behalf of the people, there must be openness and transparency about their implementation. Freedom of speech and freedom of assembly and association provide opportunities for people to participate in the creation and refinement of laws that they must subsequently live by.

This transparency and citizen participation leads to the adoption of just laws, accountability and good governance.

Free Speech and the Media

The rule of law requires freedom of speech and freedom of the media.

People must be free to comment and assemble without fear and be able to criticise the actions of government. The role of the journalists in this process is pivotal. The media remains an effective means of promoting accountability in government, and journalists play an essential role in upholding the rule of law. If their sources of information are not protected, and they themselves are open to legal action which prevents them from reporting in the public interest, the rule of law is threatened.

Uniform shield laws for journalist’s sources should be implemented across all Australian jurisdictions and should provide certainty and adequate protection for journalists and their sources.

Academic Freedom

In his paper ‘The Peter Ridd case- a pyrrhic victory for James Cook University’, Chris Merritt writes “Academic freedom is a category of freedom of speech where the public interest in protecting this right predominates.. it outweighs any assertion that people need to be protected from the risk of professional embarrassment where shoddy work is exposed…

According to Mill’s great essay, On Liberty, whilst a prohibition upon disrespectful and discourteous conduct in intellectual expression might be a “convenient plan for having peace in the intellectual world”, the “price paid for this sort of intellectual pacification, is the sacrifice of the entire moral courage of the human mind.”..

Ridd lost his personal battle. But he secured a unanimous ruling from the High Court that provides a foundation for the future defences of academic freedom. The court recognises that this doctrine has an instrumental as well as an ethical justification. It aids the search for truth in the contested marketplace for ideas. It also ensures the primacy of individual conviction- the right not to profess what one believes to be false whilst bestowing a duty to speak out for what one believes.””

Peter Ridd’s case – a pyrrhic victory for James Cook University

By Chris Merritt

This paper was delivered on May 13, 2022, at a conference organised by the Institute of Public Affairs on the future of scientific inquiry and academic freedom in Australia. Click the image to the right or click here for a PDF version of this paper.

In October last year when the High Court handed down a short, unanimous decision in Peter Ridd’s case, the true victor in this fight over academic freedom was hard to identify. Neither of the official parties would have been entirely happy with the outcome. After 27 years at James Cook University, Ridd had failed to overturn his dismissal; and the university had been left with a big legal bill and a judgement that identified its improper attempts to silence a world-class professor of physics.

Officially, James Cook University won this case. But it’s a pyrrhic victory.

The High Court broke with normal practice and refused to order Ridd to pay the university’s costs. That in itself was quite a blow: the university had been represented by Bret Walker SC, who does not come cheap. But it lost something far more important than money: the reputation of this institution has been trashed. The world has been left with the impression that this university does not understand the principle that lies at the heart of the scientific method: when searching for the truth, robust debate must prevail over courtesy. That taint will be difficult to remove.

So to describe this organisation as a winner does not capture the full impact of what happened.When viewed from Ridd’s perspective the outcome of this dispute is utterly unjust. On the substantive issue of academic freedom, he was shown to be right and the university was shown to be wrong. It was wrong to try to temper his criticism of what he considered to be shoddy science. Yet the wrongdoers still managed to salvage a victory. And one of the factors that contributed to that outcome is right out of Kafka: Ridd had failed to respect the confidentiality of an improper disciplinary process that targeted his legitimate right to engage in robust professional discourse.

On one level, the wrongdoers won after changing the terms of the dispute. They shifted it from a principled argument about academic freedom to a bureaucratic argument about the requirements of the university’s disciplinary process. Once that process was under way, the court decided that Ridd was obliged to remain silent about that process. He did not. And who could blame him? From his perspective it would have been a continuation of the university’s campaign to silence someone who had challenged the orthodoxy on global warming and the health of the Great Barrier Reef.

But there was another factor at play – one that leaves the impression that the High Court’s judgement was infected by a misconception about the nature of the argument that had been presented to the court. If that is the case, there is also a prospect that this case was wrongly decided.

But before examining that point, it needs to be made clear that this judgement falls into two halves. For Ridd, who fought to defend his right to speak robustly on matters within his field of expertise, the court’s failure to overturn his dismissal is an injustice that many will find inexplicable.

It sits uncomfortably with the other half of this judgement that consists of an entirely persuasive exposition on the importance of academic freedom and why robust debate must prevail over bureaucratic demands for courtesy and collegiality. This part of the judgement is a foundation for action by whoever happens to be education minister in the next federal government. If the next minister takes up the challenge, the real winners will be future generations – not just academics but all those who benefit from academic rigour. This part of the decision is also a warning to university bureaucrats who might be tempted to muzzle other academics.The nation’s highest court is united on the importance of intellectual freedom and, barring more judicial misconceptions, it seems inclined to side with academics should this issue again come before the court. That, of course, assumes that other academics would have the fortitude and resources to follow Ridd’s example and fight for the right to speak their mind. That is quite an assumption. In the real world, it would be a rare soul who would be prepared to risk their employment and finances in a fight over an issue of principle.

There is always a public and a private interest in protecting freedom of speech. But with academic freedom, which is a category of freedom of speech, the public interest in protecting this right predominates. It outweighs any assertion that people need to be protected from the risk of professional embarrassment when shoddy work is exposed. The public interest in exposing bad science must prevail.

That is why the next federal government needs to ensure academics will never again need to resort to private litigation to defend their right to engage in robust professional discourse. Government has a duty to protect the public interest in academic rigour.

We have already seen how government action can nudge universities in the right direction through the development of a voluntary code on academic freedom by former High Court Chief Justice Robert French. But while a voluntary code might help, it is not a silver bullet. These codes fail to take account of the fact that universities are in the business of education. And like all businesses, they are sensitive to threats to their revenue and anything that could annoy influential stakeholders. So while voluntary codes are welcome, they are unlikely to prove decisive when public discourse by academics and students is viewed as a threat to the interests of tertiary institutions.

In his 2019 review of academic freedom, French was wary of damaging institutional autonomy. He believed a statutory standard on academic freedom, beyond the level of generality currently reflected in the higher education standards made under the Tertiary Education Quality Standards Agency Act would be disproportionate to any threat to freedom of expression that exists or is likely to exist on Australian university campuses for the foreseeable future. As is well known, French favoured the voluntary approach.

But is that good enough? How realistic is it to expect a voluntary code to make a difference when academic freedom threatens relations with key stakeholders or financial backers?

This is much more than a theoretical issue: Remember Drew Pavlou? In 2020, when he was an arts student at the University of Queensland, he was suspended for two years – which was subsequently reduced to six months – for protesting against Chinese government influence on Australian university campuses.

The influence of the Chinese Communist Party within the university was a feature of the report on this incident that appeared in the Los Angeles Times. After Pavlou was jostled for his anti-China views, the US newspaper reported that on the day after the protest Chinese state media named Pavlou as a leader of the protest. The LA Times report said:

Xu Jie, Beijing’s consul general in Brisbane, praised the “spontaneous patriotic behavior” of those who had attacked him.It was an unusual statement for a diplomat, especially considering Xu’s other position: adjunct professor at the university’s School of Languages and Cultures. His dual roles were an example of the increasingly close ties between Australian universities and China, their biggest source of international students. The university didn’t chastise Xu for promoting violence. Instead, it defended its relationship with Beijing — and turned on one of its brightest students.

The Chinese Communist Party had no role in Ridd’s case but Ridd suspected other outside entities. The judgement shows he sent emails outlining his suspicion that he had offended “powerful organisations” and “some sensitive but powerful and ruthless egos”.

Five months before the High Court’s ruling, the weakness of the French code was outlined by George Williams, the deputy vide-chancellor of the University of NSW. Williams pointed out that: The code permits universities to ban people from speaking on campus where their speech is likely to “involve the advancement of theories or propositions which purport to be based on scholarship or research but which fall below scholarly standards to such an extent as to be detrimental to the university’s character as an institution of higher learning”. Universities can use this clause to limit speech that would be lawful off-campus, perhaps on topics such as climate change or vaccination. As a result, UNSW adopted the model code without this clause.

This is why the next federal government cannot allow this issue to rest. Unless the next government takes up this issue its inaction could be an invitation for another round of litigation. Those who read the judgement in Ridd’s case will find that James Cook University was wrong to censure Ridd over a 2015 email to a journalist that said the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority was grossly misusing some scientific data to make the case that the reef was greatly damaged. The same email had criticised the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies – which then complained to JCU.

The court made the point that there was no suggestion that the remarks in the email were anything other than honestly held opinions. Nothing said in that email had ever been suggested to be unlawful, defamatory, wrong or even unreasonable. Those who read the judgement will see that the university was also wrong to have censured Ridd in 2017 for remarks on Sky News in which he said it was no longer possible to trust research on the Great Barrier Reef from the Australian Institute of Marine Science and the Australian Research Council’s Centre for Excellence for Coral Reef Studies. The university was also found to be wrong to cite his remarks to Alan Jones and Peta Credlin on Sky News and tell him his intellectual freedom did not extend to criticising “key stakeholders of the university” in a manner that was not “respectful and courteous”.

Ridd’s remarks during that interview led to a declaration by the university that he was guilty of serious misconduct. Yet legal academics later came to the view that it was no more than a conventional exercise of academic freedom . So what was it that so annoyed the university’s decision-makers? In essence an academic had merely engaged in the time-honoured practice of criticising the research of other academics.

While being interviewed, Ridd affirmed remarks he had made in a book chapter which argued that the Great Barrier Reef “[q]uietly grows and waits for the beginning of the next cycle of death and regrowth”. He added that after the reef “crashes”, the “scientists … then do the same stories and push it all around the world again”. He said that “this has been going on for close to 50 years, how many more years will it take for us to cotton-on to the fact that you can no longer trust this stuff, unfortunately”. Earlier in that interview he had said: ” . . . the basic problem is that we can no longer trust the scientific organisations like the Australian Institute of Marine Science, even things like the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies. A lot of this stuff is coming out, the science is coming not properly checked, tested or replicated and this is a great shame because we really need to be able to trust our scientific institutions. And the fact is, I do not think we can anymore. “I think that most of the scientists who are pushing out this stuff, they genuinely believe that there are problems with the reef. I just don’t think that they are very objective about the science they do. I think [they’re] emotionally attached to their subject, and . . . You know you can’t blame them, the reef is a beautiful thing.”

At its core, Ridd’s fight was over his right to engage in this kind of robust discourse regardless of whether he hurt the feelings of those whose work he was criticising. This goes beyond the issue of whether the reef is or is not in trouble – however important that might be. It goes to the issue of whether it is possible for the fate of the Great Barrier Reef to be freely discussed by experts without fear of retribution.

Underlying the entire dispute were two documents that took different approaches to academic freedom. The university’s enterprise agreement granted staff the right to express unpopular and controversial views and pursue critical and open inquiry. But a separate code of conduct required intellectual freedom to be exercised with courtesy and respect – terms not found in the enterprise agreement. After considering Ridd’s statements to Jones and Credlin, the court determined they provided no basis for disciplinary action. This was a clear rejection of the university’s argument that his intellectual freedom did not justify what it said was “criticism of key stakeholders of the university” in a manner that was not “in the collegial and academic spirit of the search for knowledge, understanding and truth” or “respectful and courteous”.

Ridd lost the case for several reasons: the first is that the enterprise agreement only protected his right to make statements within his area of professional expertise and he had sent emails to external recipients that did not come within that definition. Those emails asserted that he had offended “powerful organisations” and “some sensitive but powerful and ruthless egos”, and that “our whole university system pretends to value free debate, but in fact it crushes it”.

From Ridd’s perspective, the requirement to remain silent about the disciplinary process would have been seen as an illegitimate continuation of the university’s attack on his right to express his professional opinion. He also appeared to be protected by provisions in the university’s enterprise agreement that give academics the right to “express opinions about the operations of JCU” and “to express disagreement with university decisions and with the processes used to make those decisions”.

It is therefore not surprising that he refused to play along. Had he done so, it would have meant accepting that bureaucrats had the right to muzzle an academic who, according to the High Court’s judgement, has been ranked within the top 5 per cent of researchers globally.

After the judgement was handed down Ridd described the secrecy provision of the complaint-handling mechanism as “Stasi-like”. This is what he told Andrew Bolt on Sky News: “In the end I was sick and tired of being told what I was or was not allowed to say. I knew I was taking

a risk on that confidentiality but it just had to be done. “There was no choice; I couldn’t live with myself and just shut up, which is what I would have had to have done.”The bizarre nature of this secrecy trap was not lost on those who were following this affair. Soon after the High Court’s ruling, academics from Melbourne University wrote that one way of summarising the court’s decision was that Ridd’s termination was justified by his repeated failure to respect the confidentiality of a disciplinary process that should never have been commenced.

The IPA’s Morgan Begg, writing in The Australian, came to the same conclusion. He wrote that the implication from the ruling was that the university could launch an unlawful investigation of an employee but it would be entirely lawful to force the employee to keep that investigation secret.

Logically, it seems hard to reconcile the court’s view that confidentiality should prevail over disciplinary procedures with its view, in the same judgement, that courtesy and collegiality should not prevail over robust professional discourse. On this logic, Ridd had the right to express his professional opinion discourteously but not to disclose his view that his right to do so had been violated. The secrecy trap is by no means the most troubling aspect of this decision. That honour is reserved for the reference in paragraph six of the judgement that says:

“ . . as senior counsel for Dr Ridd frankly accepted in his oral reply, the cases for both of the parties were conducted on an all-or-nothing basis. From Dr Ridd’s perspective, this forensic choice reflected the reality that, unless he was able to show that all, or almost all of the actions by JCU were contraventions of cl 14 [of the enterprise agreement] then the termination of his employment would have been justified and would have occurred in any event leaving him with little benefit had he sought to uphold only a few of the instances of declared contraventions.” [ Emphasis added]Here’s the problem: It was never part of Ridd’s pleaded case that unless he succeeded in every respect, he did not wish to prevail in any respect. The transcript of oral argument before the court shows there are just two occasions where the words “all or nothing” appear. And a reasonable reading of that part of the transcript leaves the clear impression that the reference was a statement about the logic of the parties’

construction of clause 14 of the enterprise agreement and its application to the university’s direction that the disciplinary proceedings should remain confidential. It cannot be read as a concession that none of Ridd’s claims should succeed unless all of them were successful. Yet that is how Ridd’s argument is portrayed in paragraph six of the judgement.Here is the relevant section of the transcript, which starts with counsel for Ridd, Stuart Wood SC:

MR WOOD: Some short points, if it pleases the court . . . It was never argued that the breach of confidentiality directions by themselves – in answer to Justice Edelman’s question – would constitute serious misconduct. There was no finding below that they would constitute serious misconduct and the reason for that was it was all or nothing for the University. They said we have the test right, you have it wrong, the code of conduct is the thing that governs everything, and clause 14 [of the enterprise agreement] has nothing to do with it.

EDELMAN: It was all or nothing for your client as well.

MR WOOD: Of course, of course – both ways. But if we are correct in terms of our construction of clause 14 then the directions [for confidentiality] go too far because they contravene the clause 14 rights and they also attempt to suppress – and are thereby unlawful – communication, publication of an unlawful process.” [Emphasis added]

If my reading of the transcript is correct, it suggests that the “all or nothing” reference has been misunderstood by the court as being a concession by Ridd’s counsel that, in fact, was never made. The transcript does not show that Ridd was prepared to concede every aspect of the case unless he won every separate point. Such a move would defy logic as it would not serve Ridd’s interests.

It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the exchange between Stuart Wood QC and Justice Edelman, quoted above, concerned the proper construction of clause 14 of the enterprise agreement and its application to the confidentiality directions that had been made by the university.

So if a broad “all or nothing” concession was never made, the court’s formal decision to give the university an unqualified victory must be in doubt. This is due to the fact that the judgement makes it clear that Ridd was right on the core issue of his freedom to express his professional opinion even when he did so in a robust and discourteous manner. Keep in mind that Ridd had sought a range of remedies,

including declarations, penalties and compensation. Once the limited nature of the “all or nothing” reference is properly understood, the logical consequence is that Ridd should have been entitled to at least some remedies – including formal declarations – for those actions that were taken against him by the university that the court clearly believed were unlawful. This would be the case even if his dismissal were still found to be lawful.Before leaving the “all or nothing” point, I want to make it clear that my attention was drawn to this issue by a senior lawyer who was passing on information from an even more senior lawyer. They both wanted this issue to be made public but were not prepared to put their names to this critique of a unanimous ruling by the High Court. However the hearing transcript tells the story.

The fact that Peter Ridd needed to litigate in order to defend academic freedom was the result of a form of group think that is creeping through universities not just in this country but through the traditional centres of Western civilisation. Douglas Murray, in his book The War on the West, says a new generation does not appear to understand even the most basic principles of free thought and free expression and how the scientific method has improved the lives of countless people around the world. Murray puts it

down to a cultural war within the centres of Western civilisation in which almost everything of importance that has emerged from the West is viewed with suspicion.According to Murray:

“ . . . everything connected with the Western tradition is being jettisoned. At education colleges in America, aspiring teachers have been given training seminars where they are taught that even the term ‘diversity of opinion’ is ‘white supremacist bullshit’.”So what is to be done?

Peter Ridd might have lost his personal fight, but it was just one battle in a much broader war in which freedom of speech and other core Western values are at stake. But Ridd was not fighting alone. Some of the greatest thinkers from the Western cultural tradition feature in the High Court’s judgement, including philosopher and jurist Ronald Dworkin from the United States.

What is the Rule of Law?

At its most basic level the rule of law is the concept that both the government and citizens know the law and obey it.

A good definition of the rule of law that has near universal acceptance states

“…most of the content of the rule of law can be summed up in two points:

(1) that the people (including, one should add, the government) should be ruled by the law and obey it and(2) that the law should be such that people will be able (and, one should add, willing) to be guided by it.”– Geoffrey de Q. Walker, The rule of law: foundation of constitutional democracy, (1st Ed., 1988).

The Rule of Law Wheel

The relevance of the rule of law, and an understanding of its concepts, has its origins in the Magna Carta and the Rule of Law Education Centre uses the Rule of Law Wheel to start discussion about the question “What is the Rule of Law?”

Central to the wheel and the rule of law is the concept that no one is above the law – it is applied equally and fairly to both the government and citizens. This means that all people, regardless of their status, race, culture, religion, or any other attribute, should be ruled equally by just laws.

Beyond this, the outer edge of the wheel illustrates a number of interrelated principles that reflect the rule of law in Australia, such as the presumption of innocence, and fair and prompt trials.

These principles can be considered essential elements that contribute to maintaining the rule of law. Without these, the wheel would fail to turn and Australia’s rule of law would not continue to be upheld and maintained.

Another essential element is that these principles and Australia’s rule of law is supported by informed and active citizens. Without responsible and engaged citizens, society is unable to work together to uphold important principles and values which support our rule of law and democratic society.

https://www.ruleoflaw.org.au/what-is-the-rule-of-law/

On the day of the ruling, education minister Alan Tudge made the point that 41 universities had aligned their policies on free speech with French’s model code. In the view of the former Chief Justice academic freedom is a defining characteristic of universities – an assessment that was cited by the High Court along with the classical defence of free speech by John Stewart Mill.

According to Mill’s great essay, On Liberty, whilst a prohibition upon disrespectful and discourteous conduct in intellectual expression might be a “convenient plan for having peace in the intellectual world”, the “price paid for this sort of intellectual pacification, is the sacrifice of the entire moral courage of the human mind”.

When we look a little deeper at French’s report on academic freedom, the former Chief Justice makes it explicit that the idea of academic freedom has roots that go all the way back to the heart of Western civilisation, ancient Greece.

According to the French report:

“The ideal of academic freedom can be traced back to Socrates’ defence in Plato’s Apology, before the Athenian people, of his right to discuss controversial topics with others, that those in power found unacceptable.”Despite George Williams’ concerns about the shortcomings of French’s model code, there is no doubt it is a step in the right direction. However there clearly need to be more steps. More than two years before the judgement, Ridd praised the code and called for it to be made mandatory at all universities, not voluntary.

Alan Tudge knows this fight is not over. On the day of the judgement the education minister recognised that in some places there is a culture of closing down perceived “unwelcome thoughts” rather than debating them.

This is line with Williams’ concern that governments and public institutions have become less tolerant of freedom of speech and more willing to deny people their voice. He attributes a good part of the problems to the nation’s parliaments that have enacted an ever-growing list of anti-speech laws.On free speech, Williams is the polar opposite of the bureaucrats at James Cook University who tried to silence Ridd. Williams believes freedom of speech on campus should be no different to freedom of speech everywhere in Australia. The only constraints should be those that apply under the normal law such as defamation. But while Ridd favours a mandatory code on free speech at universities, Williams goes much further. He believes the entire community needs stronger protection for freedom of speech.

According to Williams:

“We need a free speech statute that applies across our society to provide every person with a right of free expression. This should apply a common standard to universities and other parts of our society to ensure consistent and effective protection for a vital democratic value.”The conduct of James Cook University is not an isolated incident. It is part of a cultural war that is being fought in those countries that have been built on core ideas from the Western tradition. Free speech is one of those ideas, but so is religious liberty and, most importantly, the rule of law. But all of those freedoms depend on the first – freedom of speech.

Ridd lost his personal battle. But he secured a unanimous ruling from the High Court that provides a foundation for the future defence of academic freedom. The court recognised that this doctrine has an instrumental as well as an ethical justification. It aids the search for truth in the contested marketplace for ideas. It also ensures the primacy of individual conviction – the right not to profess what one believes to be false while bestowing a duty to speak out for what one believes.

The starting point for future battles will be the voluntary codes. But ranged against them is the reality that universities have powerful stakeholders that can influence these organisations in a variety of ways.

One former vice-chancellor told me that those in charge of the nation’s universities are, in the main, terrified that their staff will do or say something that could jeopardise commercial relationships or imperil future grants. In this person’s assessment, that is merely part of a broader problem in which academics who challenge the dominant paradigm risk being sidelined.

Group think, in this person’s view, is just as big an enemy of academic freedom as the institutional self-interest of universities. Robert French was clearly right to be wary about eroding the autonomy of the universities. But that horse has already bolted. The autonomy of these organisations has already been abridged by influential outside stakeholders – just as Ridd feared.

Also at play are the contending forces of the cultural war that is under way within the nations of the West. The challenge confronting the next federal government is to decide how to ensure these influences do not undermine academic freedom. Is it good enough to limit academic freedom to discussion within a person’s area of expertise? Such an approach still accepts that universities can legitimately stifle public discussion, and will encourage timidity.

The next federal government might do well to re-examine George Williams’ proposal for broader statutory protection for free speech regardless of whether it takes place on campus, in academic journals or on television. The next government might also care to revisit the definition of of academic freedom that French had proposed in his report. It included a several uncontroversial elements as well as components that would protect statements inside an academic’s field of expertise.

French had also included one provision that would have endorsed the right of academics to speak freely in their personal capacity on any issue without constraint by their employer. This provision says academic freedom includes:

“The freedom of academic staff, without constraint imposed by reason of their employment by the university, to make lawful public comment on any issue in their personal capacities;”This would have eliminated the risk that future disputes would turn on the question of whether statements are permissible because they are within an academic’s area of expertise or impermissible because they fall outside a notional boundary. By protecting “lawful public comment on any issue” the

French proposal would have eliminated that boundary. It would therefore also have eliminated the risk of litigation over have extent of the boundary. It would have prevented university bureaucrats from attempting to regulate public statements academics might make in their personal capacities.So what happened to that proposal? In March, 2021, federal parliament approved amendments to the Higher Education Support Act to implement recommendations from the French report, including the report’s definition of academic freedom. Every element of French’s proposed definition was included in the amendment – except the provision outlined above that would have protected lawful public comment on any issue.

The amendment was made in the Higher Education Support Amendment (Freedom of Speech) Bill 2020. The explanatory memorandum to the bill says: “The statutory definition in Item 4 closely aligns with the definition in the French Model Code but includes a minor technical modification recommended by the University Chancellors Council, in consultation with the Honourable Robert French AC. This modification excludes from the definition “the freedom of academic staff, without constraint imposed by reason of their employment by the university, to make lawful public comment on any issue in their personal capacities” element of the Code definition. This element of the definition was more appropriately considered to fit within the ambit of a broader societal freedom, referred to in the Model Code as “freedom of speech”, rather than within the narrower concept of “academic freedom”.

The decision to eliminate part of the proposed definition of academic freedom might have served the interests of the University Chancellors’ Council but it has reduced the potential benefits for academics.

When a future education minister addresses this issue, the thoughts of Ronald Dworkin, as embraced by the High Court in the Ridd judgement, could be a sound guiding principle:

“The idea that people have that right [to protection from speech that might reasonably be thought to embarrass or lower others’ esteem for them or their own self-respect] is absurd. Of course it would be good if everyone liked and respected everyone else who merited that response. But we cannot recognize a right to respect, or a right to be free from the effects of speech that makes respect less likely, without wholly subverting the central ideals of the culture of independence and denying the ethical individualism that

that culture protects.”References

Peter Vincent Ridd v James Cook University [2021] HCA 32 at paragraph 6, 31, 48

High Court transcript, Peter Ridd v James Cook University [2021] HCATrans110, page 53, at 2355, 2360 and 2365

Robert French, Report of the Independent Review of Freedom of Speech in Australian Higher Education Providers, page 114, 222, 231

Los Angeles Times, An Australian student denounced his university’s ties to China. Then he became a target, December 21, 2020

George Williams, Free speech code for unis should apply nationwide, The Australian, June 7, 2021

Joshua Forrest and Adrienne Stone, The High Court’s defence of academic freedom in Ridd v JCU, Australian Public Law, 5 November 11, 2021

Peter Ridd, Sky News, October 13, 2021

Joshua Forrest and Adrienne Stone, The High Court’s defence of academic freedom in Ridd v JCU, Australian Public Law, November 17, 2021

Morgan Begg, Ruling against Ridd shines light on cancel culture, The Australian, October 13, 2021

Douglas Murray, The War on the West: How to Prevail in the Age of Unreason, Harper Collins, as extracted in The Australian, April 30, 2022

John Stewart Mill, On Liberty. 13

Peter Ridd, Robert French’s code is a beacon for freedom of speech, The Australian, April 26, 2019

Explanatory memorandum, Higher Education Support Amendment (Freedom of Speech) Bill 2020, page 10

Ronald Dworkin, We need a new interpretation of academic freedom (1996) 82(3) Academe 10 at 14, as cited in Ridd v James Cook University [2021] HCA 32